Writer Amy Jo Burns thought meeting her future husband’s family would be easy—three years of road trips proved otherwise.

On the first road trip Rajan and I took together, he packed an old jelly jar of curry spices his mother had mixed for him. We drove six hours west on I-80 from Queens, where his family lived, to the small town in western Pennsylvania where I grew up. He would be meeting my extended family for the first time. We were twenty-two, freshly graduated from college, and crazy about each other. That weekend, he cooked a large pan of chicken curry for a crowd of fifteen people, many of whom had never met an Indian American before.

The kitchen was stuffed with my loved ones, each asking Rajan about his favorite sports teams, his major, his job prospects, all while he cooked. He also made poori—puffed and fried wheat bread, each piece rolled out by hand. I offered to help, but Rajan didn’t want it.

“This is for you, too,” he said.

The situation would have intimidated even a seasoned cook, but not Rajan. He’d never made curry and poori before, and he’d written his mother’s instructions down on a scrap of paper I still have in my recipe box. ½ finger’s length ginger, it reads. A few onions.

How Do I Make Sure the First Trip With My Partner Is a Success?→

Just before he served it, he realized he’d forgotten salt. He started to spread it liberally across the plated meat, and I touched his hand.

“Not too much,” I said.

My dad’s best friend slapped my hand away. “Let the man cook,” he said.

Everyone ate and helped themselves to seconds. Each of us took turns scraping the pan.

This was my Rajan: intrepid maker of feasts, winner of hearts.

“The situation would have intimidated even a seasoned cook.”

We were friends first—taking early evening walks through autumn leaves on our university’s campus in upstate New York, learning to rollerblade and falling together in a twisted heap on the sidewalk, pretending to study side by side at the library. Rajan was funny and laid-back, thoughtful and tender—an engineer who liked listening to a shy girl like me recount the plot of Jane Eyre more than once.

It was snowing the evening of our first date in February of our senior year, four months before I took him home to meet my family.

“I’m falling in love with you,” he said to me as soon as we sat down at our table. “Do you feel the same way?”

A hush fell over the restaurant as every diner seemed to stop and look at us. It was the boldest and most romantic thing anyone had ever said to me.

The next month, Rajan took me by bus to meet his parents, and we cheered for the Mets at their frigid season opener. His mother showed me her sewing projects and taught me how to make beef cutlets. He showed me his New York City: the barbershop he liked on Jamaica Avenue, the best views from the J train, and the legendary Indian buffet at Jackson Diner.

Rajan and I loved how wonderfully strange it felt to bring each other home. Both trips gave us unexpected firsts: Rajan played his first game of cornhole, and I got pooped on by a city pigeon. We were so eager to stretch toward each other that we assumed our families were ready to stretch, too. Meeting family is one thing; becoming family is another. We thought our trips home had been a success—until we each went home alone.

The World’s 10 Thirstiest Cities, According to Tinder→

In the weeks after our visits, my parents had heard from an ill-informed friend that Indian husbands beat their wives. Rajan’s mother told him if we got married, then we’d end up divorced, because that’s what white people did. In short, our families liked us separately, but they didn’t love us together.

To me and Rajan, being an interracial couple had never been the most interesting or essential thing about us. But to everyone else, it was.

“Meeting family is one thing; becoming family is another.”

After we’d been dating for six months, a few other interracial couples we knew had broken up because of the same kind of family tension Rajan and I were experiencing. Ending the relationship never felt like an option for us, but we still felt stuck. We started to see how much easier it might be to live segregated lives.

On a Sunday afternoon in autumn, Rajan took me out for pancakes. Before we entered the restaurant, we sat in his red hatchback and considered our options. We could compartmentalize our lives by spending our private time together, and our family time apart. Holidays, birthdays, weddings, each with our own people. It would alleviate the friction we felt, but what if it also meant he and I would never feel like family to each other?

“The thing is,” I told him, “I know you’re the one. My other half.”

His eyebrows shot up. “I don’t believe in soul mates.”

“You don’t?”

His words stung. I believed in one-person-for-everyone, fairy tale kind of romances. He’d given one to me. I was shocked he didn’t believe in them, too.

“Think about it,” he said. “What about every person who is widowed, divorced, remarried? If one person gets it wrong, it’s like dominoes. Then it’s messed up for everyone. It makes no sense.”

“What if it meant he and I would never feel like family to each other?”

We sat in silence for a minute. Rajan could feel my disappointment.

“I choose you,” he said, wrapping his hand around mine. “And that’s better than fate.”

So Rajan and I made a commitment—anytime either of us took a trip to see family, we went together. We put almost six thousand miles on my Chevy Lumina from trips to his home and mine. More than 390 miles separated our two families. We also had vastly different cultures, customs, and prejudices. Rajan and I had no idea what it might take for our families to fall in love with us, but we tried to help them along, one road trip at a time.

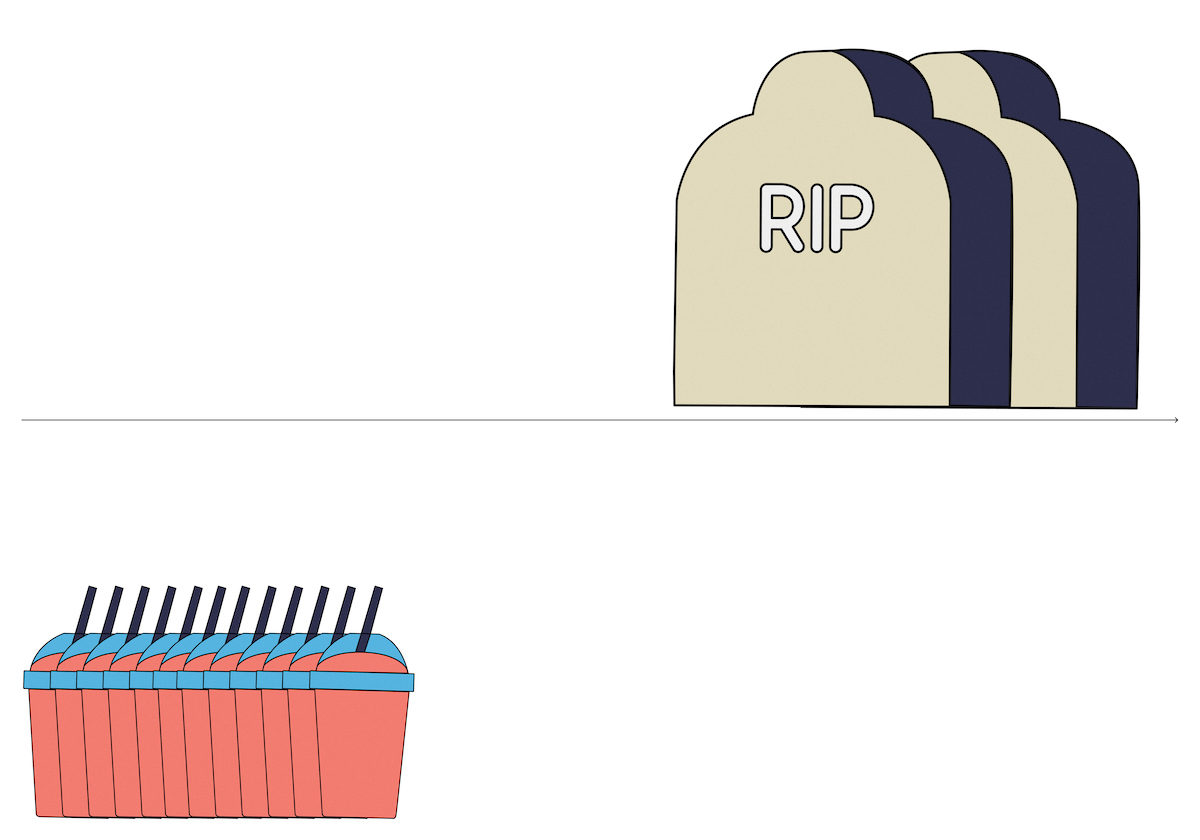

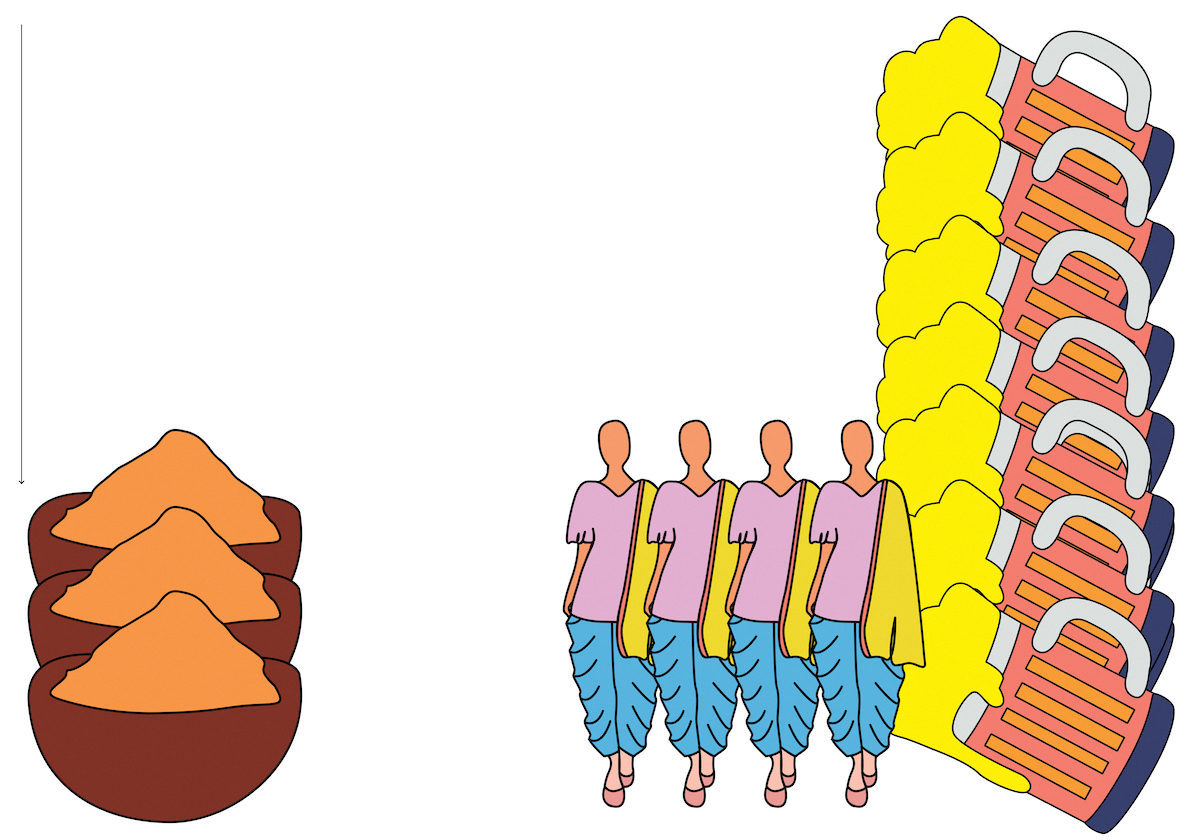

For three years after we graduated from college, we took four different cars on countless holiday celebrations, through countless traffic jams, to sixteen weddings, two funerals, and ten births (seven nieces, three nephews). We drank twelve Slurpees, ate eighteen Dairy Queen Blizzards, and downed twenty-five bottles of Cherry Coke. I botched one attempt at making samosas, which Rajan’s family ate anyway, and my family made at least six comments about the Obama sticker on Rajan’s car. We got one ticket for a broken taillight (and four almost-tickets for speeding). I took four trips to Indian clothing stores so Rajan’s sisters could buy me a salwar, while my mother baked four chocolate amaretto cakes to cure Rajan’s sweet tooth. We had seven fights over whose family we would spend the upcoming holiday with, and went on fifteen visits to our respective churches, one Presbyterian and one Marthomite. There were five disputes over presidential candidates, and twelve debates over CNN vs. Fox News. We listened to thirty-two Mets games on AM radio, and I was sent home with fourteen plastic containers of homemade beef curry. There was one racial slur; two difficult conversations about it. We made over fifty calls to our parents once we’d reached our apartments safely, and just as many about when we’d be coming back.

Those road trips taught us a lot about each other. I told Rajan I dreamed of becoming a writer, and he shared how much he wanted to be a dad. We talked about the memories from home we wanted to keep, and those we hoped to leave behind. In time, our families saw that in coming together, Rajan and I wouldn’t abandon what made us unique. The more we celebrated our differences, the more our families did, too.

Flying Solo: A Break-Up Trip to the Honeymoon Capital of the World→

At the end of those first three years, Rajan took a solo road trip of his own. I was on vacation with my family at the Outer Banks in North Carolina, and after we talked on the phone one evening, Rajan drove through the night to surprise me on the beach the next day. My whole family was in on it. He proposed, and I said yes. We took a sunset trip just the two of us, by boat this time, to Ocracoke Island, where we watched for wild horses until the sky went dark.

Nine months later, we got married in the hills of western Pennsylvania. I wore both a white dress and a sari at our wedding. We incorporated traditions from both our faiths into the ceremony. We ate chicken curry and pasta at the reception. Rajan forgot his credit card in the pants of his tuxedo, so the morning after the wedding we had to turn around and drive all the way back after we were halfway home to New Jersey. We started our marriage just as we’d started our relationship: driving.

“In time, our families saw that in coming together, Rajan and I wouldn’t abandon what made us unique.”

Our wedding was a wonderful day, but it was just that: a day. We’ve been married for thirteen years, and our road trips haven’t stopped. We travel for every holiday. We still fight sometimes about where to spend them. The trips have become easier in some ways—we know we’ll stop at Exit 173 on I-80 for gas, we know to avoid Friday afternoon traffic on summer weekends—and they’ve become harder in others. We travel now with two car seats, one Pack ’n Play, four pairs of sunglasses, and a huge supply of diapers. We have to stop more often, and we get tired more easily, but our families are always waiting by the window for us to arrive.

We’re learning there isn’t a point of arrival where love is concerned. That horizon at the end of the road keeps beckoning, and for as long as we’re able, we’ll keep driving toward it.

A version of this story appeared in Here Magazine issue 12. Amy Jo Burns is the author of the memoir Cinderland and the recently published novel Shiner, from Riverhead Books. Her writing has appeared in The Paris Review Daily, Tin House, Ploughshares, Electric Literature, and more.