Before the rise of the Third Reich, Berlin was a magnet for sex, drugs, and counterculture of every stripe—and English author Christopher Isherwood, best known for Goodbye to Berlin, fell wholeheartedly into its orbit.

Though the city has had many different personalities since the 1930s, modern-day Berlin, with its flourishing queer, club, and art scenes, would seem to have the most in common with the era of the Kit Kat Klub.

Below, a guide to English writer Christopher Isherwood’s Berlin as imagined for Here Issue 10 by a local writer who examined the novelist’s beloved haunts, and set out to discover where Isherwood and his ol’ chums would hang about if they were around today.

The English writer Christopher Isherwood never did as he was told. Before he became one of Berlin’s defining literary voices, Isherwood defied his mother’s wishes by moving to the German capital in the first place—a choice he made because, as he writes in his autobiography, Christopher and His Kind, “Berlin meant boys.” Tsk tsk.

So he boarded the day-long train from London to Berlin, sojourning for just a few weeks at first but eventually spending nearly two and a half years in the Schöneberg flat he shared with a dozen other lost souls. It was in that apartment that Isherwood met Jean Ross, the successful journalist and activist who wished instead for a life as a cabaret artist. Ross would be the inspiration for the character Sally Bowles, most famously brought to life by Liza Minnelli in Cabaret, the film inspired by Isherwood’s novel Goodbye to Berlin. (Ross wasn’t so good at singing and dancing, as it would turn out, though the stage and screen renditions of Ms. Bowles suggested otherwise.)

Isherwood’s strength as a writer bloomed with his observations of people like Ross, and of other young gay men who “found” themselves in Berlin. He kept diaries of his daily life, blending in to the background of this cinematic setting in order to maintain a critical, curious eye. Hence: “I am a camera.” And what a time to witness: This was at the height of Magnus Hirschfeld’s monumental and conclusive research on homosexuality, which paved the way for our understanding of gender variance and for the first gender-affirmation surgeries.

“I only know about the future that, however often and however variously I have imagined it to myself, the reality will be quite different.”

Hirschfeld’s libraries were burned by the Nazis on May 6, 1933. He was out of town on tour, and never returned to his home in Berlin. Isherwood would leave one week later on May 13, writing, “And now the day which seemed too good, too bad to be true, the day when I should leave Germany, has arrived, and I only know about the future that, however often and however variously I have imagined it to myself, the reality will be quite different.”

Today, many sad realities later, Berlin is thriving in a way Isherwood had never dreamt possible. He died on January 3, 1986, three and a half years before the wall fell and reunited both a war-torn Berlin and the whole of Germany. In the decades to follow, underground music and a “never again” mantra have turned Berlin inside out, attracting bon vivants and revelers, young artists and creators, and queer people from around the globe.

This city wears its scars openly as a declaration of healing, and as a way to honor the people like Isherwood, Hirschfeld, and Ross, who took to this global city and in turn made the world a lot more like Berlin. Below, find some of the threads that connect past and present.

The “Then” Neighborhood: Schöneberg

Sure, “Berlin meant boys,” but specifically, it was the Schöneberg neighborhood where these young men flocked (and it’s in this part of town where you can find Isherwood’s former residence at Nollendorfstraße 17). Schöneberg was the epicenter of the gay scene during the Weimar Republic, and arguably remains so to this day. However, it’s unlikely that Isherwood would find himself hanging out there now, since the 1920s-and-’30s cast of queers was more transient, transgressive, and colorful than Schöneberg’s residents today. That’s not a knock: Schöneberg is a gay man’s utopia, with rainbow flags and sex shops and leather daddies at every glance. But more permanent, established residents live there today; these men have known each other for years and never intend to leave.

The “Now” Neighborhood: Neukölln

There is no single cluster of young queer people in Berlin these days; they span the city in search of affordable housing since the more established central neighborhoods are in high demand. The neighborhood that has changed the most in recent years due to the influx of young creatives is Neukölln. Fifty years ago this would have been laughable; then, much of Neukölln was still operating on Weimar-era plumbing, with all residents of a building sharing single toilets. But it’s this historic charm that has attracted many to the area. Today, Neukölln belongs to a wonderful cross-section of outsiders: Along with its youthful queer class, this is the heart of the city’s Turkish and Arab populations, many of them refugees from crises in Syria, Lebanon, Palestine, Iraq, and Libya. This is as Berlin as it gets. (And the best dinner in town is at the Lebanese restaurant Azzam.)

The “Then” Pub: Noster’s Cottage

Located at Zossenerstraße 7, Noster’s was the first bar Isherwood visited in Berlin, accompanied by his friend, the poet W. H. Auden. It was technically called “Noster’s Restaurant zur Hütte,” though both men referred to it as the Cozy Corner in their works. If it had been void of patrons, Noster’s Cottage would have felt stale, adorned only with photographs of bicyclists and boxers. But it was the patrons themselves—handsome, lonely men with “their shirts unbuttoned to the navel, and their sleeves rolled up to the armpits”—that attracted our hero. Many of them would engage patrons like Isherwood and Auden—often for a fee as handsome as their faces. Such was the reality for this community a century ago: The best bars were marketplaces of for-hire love.

The “Now” Cafe: Hallesches Haus

Nothing for rent here: The only marketplace at Hallesches Haus is its general store, where cafe patrons can top off their shave creams and browse table lamps. Otherwise, this brunch and freelancer hotspot, located at Tempelhofer Ufer 1, is one of the most visited by the local caffeinated crowd, thanks to its fresh, hipster-friendly salads, open-faced sandwiches, generous wine pours, and pop-ups (like barbershops, yoga classes, and food vendors). It’s about as opposite as something can be from a 1928 Rent-Boy bar, but it’s exactly the kind of place two starry-eyed queer writers would meet for a drink, in search of like-minded eye candy in modern-day Schöneberg.

The “Then” Club: The Eldorado

If you pass the intersection of Kalckreuthstraße and Motzstraße in Schöneberg today, you’ll find a natural grocery store (biomarkt), called Speísekammer im Eldorado. Besides that name, you’d never know that this was once the location of the storied Eldorado, a chandeliered, all-inclusive queer bar and club. Eldorado supposedly inspired the Kit Kat Klub, as depicted in Cabaret. (Not to be confused with the modern-day, real-life KitKatClub, one of Berlin’s most notorious spots for, uh, “adventure” tourism.) A frequent host to performers like Marlene Dietrich and Claire Waldoff, this is where the queer men of the era could dress and behave however they wanted, be it effeminate or female-presenting. You could even buy coins from the bar and exchange them for a dance with any of the mainstay women—or men dressed as.

The “Now” Club: SOUNDS

Much of Berlin’s current scene revolves around music, plus nightlife that spans multiple nights—and days. The queer scene is no exception and is a natural home for people of all expressions. SOUNDS is a new club in the southeast corner of Neukölln, and quickly gained speed for its excellent lineup of DJs, rotating parties, and inclusive aura. You’ll see trash drag (that’s a thing, yes), diversity in patrons, and will feel like you’re at the center of something significant, something exemplary. While much of Berlin’s nightlife involves hours-long queues and turn-away at the door if you aren’t in proper “Berlin attire,” SOUNDS is come-as-you-are, with a baseline of open-mindedness and a propensity to dance.

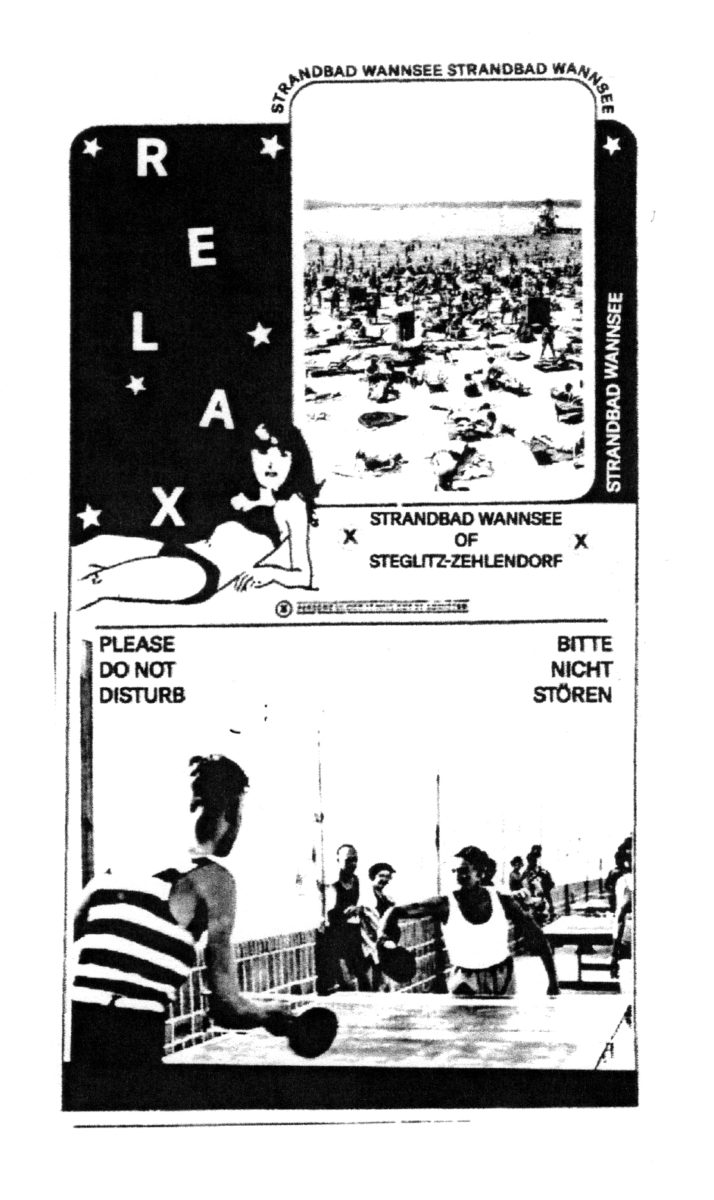

The “Then” and “Now” Lake: Strandbad Wannsee

Landlocked as it is, Berlin isn’t parched. In the summer, its residents fan out to the perimeter, as the region is populated with beach-lined lakes. On the southwest edge, on the border with Brandenburg, is Strandbad Wannsee, which attracts Berliners of all types—families, lovers, friends, plenty of them queer. Isherwood and his lover Otto would ride the bus here during Berlin’s heatwaves and sprawl out amongst the nearly one million visitors to the beach each year. It’s a favorite pastime of residents to this day since you can nap to your heart’s content on loungers, cool off in the water, play volleyball with friends, or even sun your buns on the nudist portion of the beach. (Germans have no hang-ups when it comes to nudity, it should be known.) If you’re in need of leisure on your visit, Strandbad Wannsee is most easily accessed via S-Bahn 1 and 7.

Weekly tours of Isherwood’s neighborhood are available through isherwoods-neighbourhood.com.