There have always been plenty of reasons to travel to Dallas, but dining wasn’t necessarily one of them. Now, Dallas restaurants are finally getting the recognition they deserve, reshaping a once pretentious and tedious dining scene into a worthy culinary destination that’s as diverse as it is accessible.

DALLAS READY

I grew up in Texas, and my family has a saying: There’s “getting ready” to go out, and then there’s “getting Dallas ready.”

Cue the hair spray, fake nails, shoe shine, and well-tailored attire. You know, fashion inspired by the sensational (and aptly named) 1980s soap opera Dallas. In my mind, the city was where you got dressed up to go out for a nice if uninspired sirloin, or as Chef Julian Rodarte of Beto & Son, an Insta-worthy Mexican restaurant in Dallas’s Trinity Groves, puts it: “the three food groups of Dallas: barbecue, Tex-Mex, and steakhouses.”

Dallas was the kind of city you went to for its big-box shopping (Neiman Marcus was founded here in 1907) or art scene (Dallas boasts the largest urban arts district in the country). Dallas is also home to six major league sports teams (how about those Cowboys?). In other words, there have always been plenty of reasons to come to Dallas, but the culinary scene wasn’t exactly one of them. Much like the soap operas, it lacked substance.

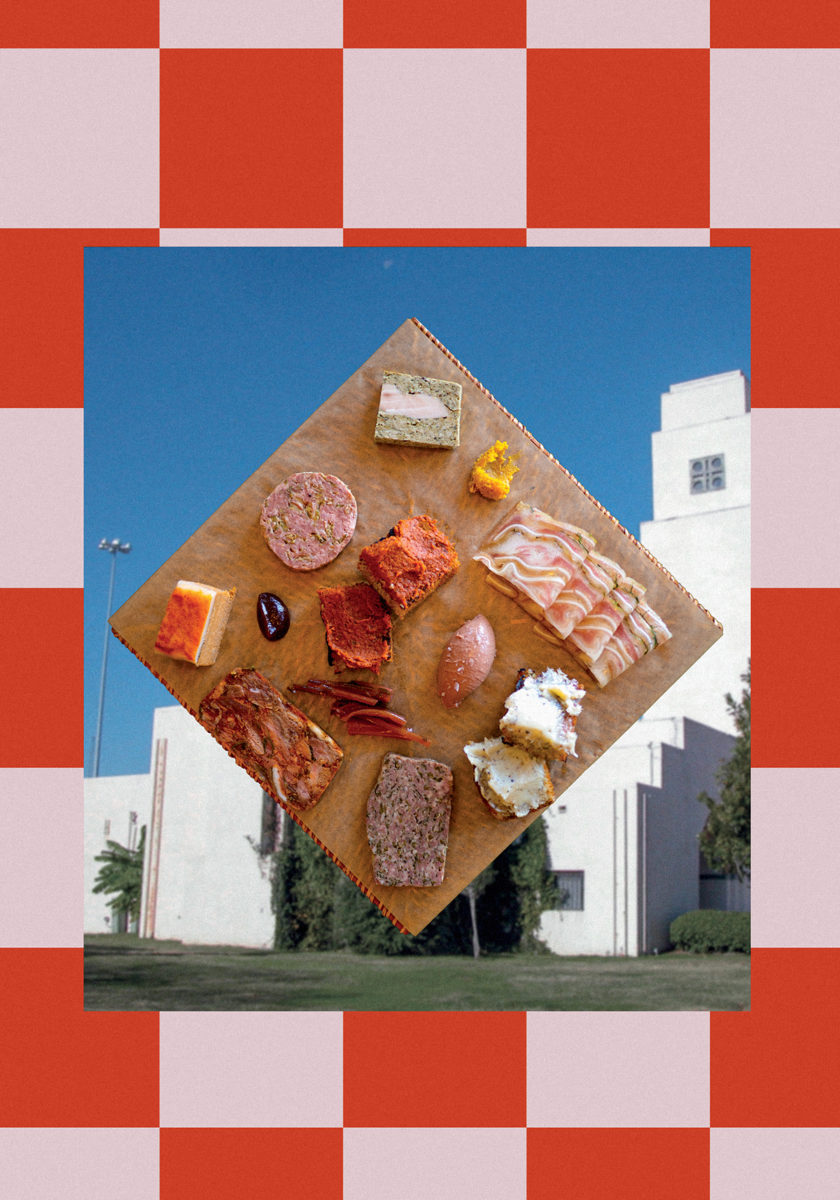

So imagine my surprise when Bon Appétit named Dallas their 2019 Restaurant City of the Year—especially when other Texas cities like Austin and Houston have long been known for stellar dining options. But there on the glossy pages of Condé Nast’s premier food publication was a Laotian restaurant serving up khao soi (spicy egg-noodle soup) and deep-fried tripe chicharrones, a playful charcuterie board from a place called Petra & the Beast with meats marbled into pâtés like abstract art, and a speakeasy behind a bridal shop lauded for its creative, mezcal-forward cocktail menu.

“People think of Dallas as just a bunch of pretentious cowboys and cowgirls.”

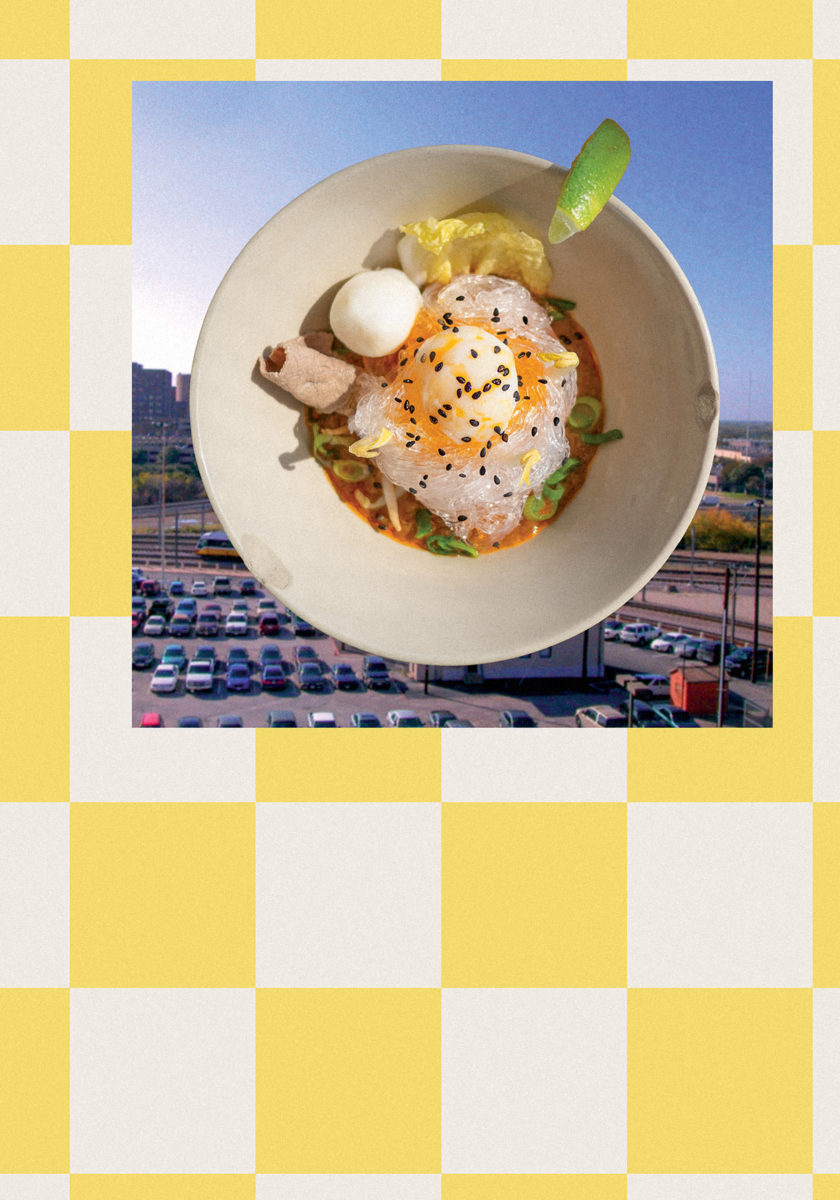

This was not the Dallas I thought I knew—bougie, fancy, and whitewashed—and I wasn’t alone in my surprise. “People think of Dallas as just a bunch of pretentious cowboys and cowgirls,” says Donny Sirisavath, owner of the aforementioned Laotian hotspot known as Khao Noodle Shop. “But Dallas is one of the fastest-growing cities in the country. We have a lot of different cultures from the East Coast, West Coast, immigrants, and then of course [people] from Texas as well.”

What I discovered during my four-day trip is a dining scene with a rapidly expanding identity that stays true to certain roots, while reinventing what it means to dine well in Dallas.

KITCHEN CONTINENTAL

To truly understand and appreciate the Dallas restaurant scene, we’re going to have to go back to the ’80s (the Dallas soap opera heyday). Back then, there were restaurants beyond the “three food groups of Dallas,” but they were mostly confined to the upper echelons of fine dining.

“There were a number of good restaurants in town, but they were all French or quote-unquote ‘continental,’ which is the word you used back then to mean ‘worldly,’” says Chef Stephan Pyles, a fifth-generation Texan who opened his first restaurant in Dallas in 1983. “It’s what you said if you wanted to sound fancy and jack up the menu prices.”

If Dallas was seen as a kind of culinary downer, Chef Pyles was one of the few actively combatting that reputation. Leading fine dining beyond the Eurocentric palate, Pyles opened a restaurant called Routh Street Cafe in 1983, and quickly garnered attention for bringing his French culinary training to Southwestern ingredients. Pyles went on to open 23 restaurants in six states, with critics dubbing his cooking “New Texan Cuisine,” and he became the first to be awarded Best Chef in the Southwest category by the James Beard Foundation.

At the time, fine dining was a safe space to experiment. It was where chefs were free to be more creative and educate and push diners beyond what they thought they knew about food.

“Good food in this country has only been around for a little more than a generation,” says Pyles. “Before the ’80s, there was nothing. There wasn’t the interest. After World War II, we lost our way in terms of quality, preparation, and emphasis on good raw ingredients, and so the ’80s was all about rediscovering that. It was happening all over the country, and I was able to help lead that movement in Dallas and Texas more generally.”

But relegating sophisticated and experimental cuisine to fine dining meant it wasn’t always accessible. And as diners became more educated and adventurous, they started to look beyond white tablecloths.

NO STARS FOR LONE STARS

Fast-forward to January 2020: News broke that Pyles would be closing the doors to his critically acclaimed Dallas Arts District restaurant, Flora Street, after just two years in business. It was a bit of a shock—here was one of the biggest culinary names in Dallas, with several decades of history in the city, who had created a restaurant that had all the trappings of a Michelin-star experience.

The menu at Flora Street strove for a delicate balance of Southwestern, Latin, and modern American cuisine, bringing out the best of Texas in a sleek fine-dining environment—crystal chandeliers, French plates, Italian silver. Flora Street was designed to be Pyles’s swan song, an attempt to return to the magic of Routh Street Cafe with all he had learned over the last four decades.

It was well-known among staff at Flora Street that the restaurant had an underlying mission to draw the Michelin Guide to Dallas, but even one of the country’s most celebrated chefs could not persuade the meticulous restaurant-raters. Meanwhile, the city’s restaurant scene was evolving beyond the scope of the elusive stars, which begs the question: Does Dallas really need Michelin to legitimize its dining scene?

Flora Street’s closing doesn’t exactly mean the end of an era. Pyles sees himself as a torchbearer to the new generation of modern Texan chefs. “You can’t walk into a restaurant in Dallas where I don’t know half the staff, from busboys to dishwashers to chefs. I feel like the University of Pyles sometimes,” he says. “If they haven’t worked for me, they have worked for somebody that’s worked with me.”

One such example is Matt McAllister, who worked for Pyles for many years before opening his hotspot Homewood in Dallas’s Oak Lawn neighborhood. The sophisticated menu, which emphasizes slow-roasting and cooking over embers, redefines familiar comfort foods (think half chicken with creamy grits and thyme jus) in a refreshingly casual atmosphere—and landed him on Texas Monthly’s 10 Best New Restaurants in Texas list last year. McAllister also employed one Misti Norris, who now helms Petra & the Beast. Both chefs have received James Beard nods in recent years for taking their culinary creativity to new levels outside the confines of fine dining.

“The national zeitgeist has placed so much more emphasis on restaurants that are international and not upscale, but just very, very interesting. Often restaurants that have been started by immigrants,” says Pat Sharpe, Texas Monthly’s food editor, who’s put nearly 45 years into the magazine’s restaurant section and seen the ebbs and flows of many a dining trend.

“Dallas is finally becoming the city we always thought we were,” Pyles adds. “We always kind of assumed we were this cosmopolitan place, and I don’t think we were necessarily, but it looks like it’s kind of happening now.”

Perhaps it’s not Dallas that’s changing so much as our idea of what it means to be “cosmopolitan.” At the very least, you won’t find the term “continental” on the menus of Dallas’s new guard.

*CHEF’S KISS*

I pull up to a dimly lit corner establishment in Old East Dallas. The parking lot is full but there’s no signage, no boisterous music pulsing from the covered windows. I double-check my Google Maps route: Yes, this has to be Petra & the Beast.

Thankfully, the interior is warmly lit and inviting, despite its lack of frills (I later learn we’re in a converted former gas station). Dried flowers hang from the ceiling. An industrial-sized refrigerator full of condiments hums in the background. I pull up a chair at a communal table and ask the people sitting next to me, who both happen to be local chefs, what I should order. The giant chalkboard menu, led by Chef Norris, is intriguing if unfamiliar—its small plates change frequently, feature only local ingredients, and utilize every last speck of any food product brought into the kitchen, which is why you might find uniquely flavored salts or something called “fall vegetable dust” topping your dish.

“You don’t get many people who are really innovative, who are really coloring outside the lines,” says Texas Monthly’s Sharpe. “And I think Misti is one of those.”

I would have to agree—from the playful charcuterie board to inventive small plates like pickled and raw shaved beets held in smoked syrup with Griffin cheese mousse, fresh dill, peanut brittle, and yes, “fall vegetable dust,” the menu at Petra & the Beast is much more than its “new American” classification could ever invoke.

“Dallas is finally becoming the city we always thought we were.”

“In the past, [Dallas] wasn’t as supportive of some of the more diverse restaurants, not because we didn’t like them, but because we gravitated towards what we were familiar with,” says Beto & Son’s Chef Rodarte. “But in most recent years we have started gravitating towards what we’re not familiar with, and I think that’s allowed other kinds of restaurants to rise up in the mix. Now we have a bunch of really talented people that come from all these different diverse backgrounds opening really unique restaurants.”

But how does such ingenuity affect the broader Dallas restaurant market? After all, it would be a missed opportunity to come all the way to Texas and not eat some great Tex-Mex. “I think it causes restaurants like [Beto & Son] that are in the more familiar Mexican market to find more diverse ways to present and do things, because that’s what people are looking for,” Chef Rodarte posits. “It pushes the creativity of chefs.”

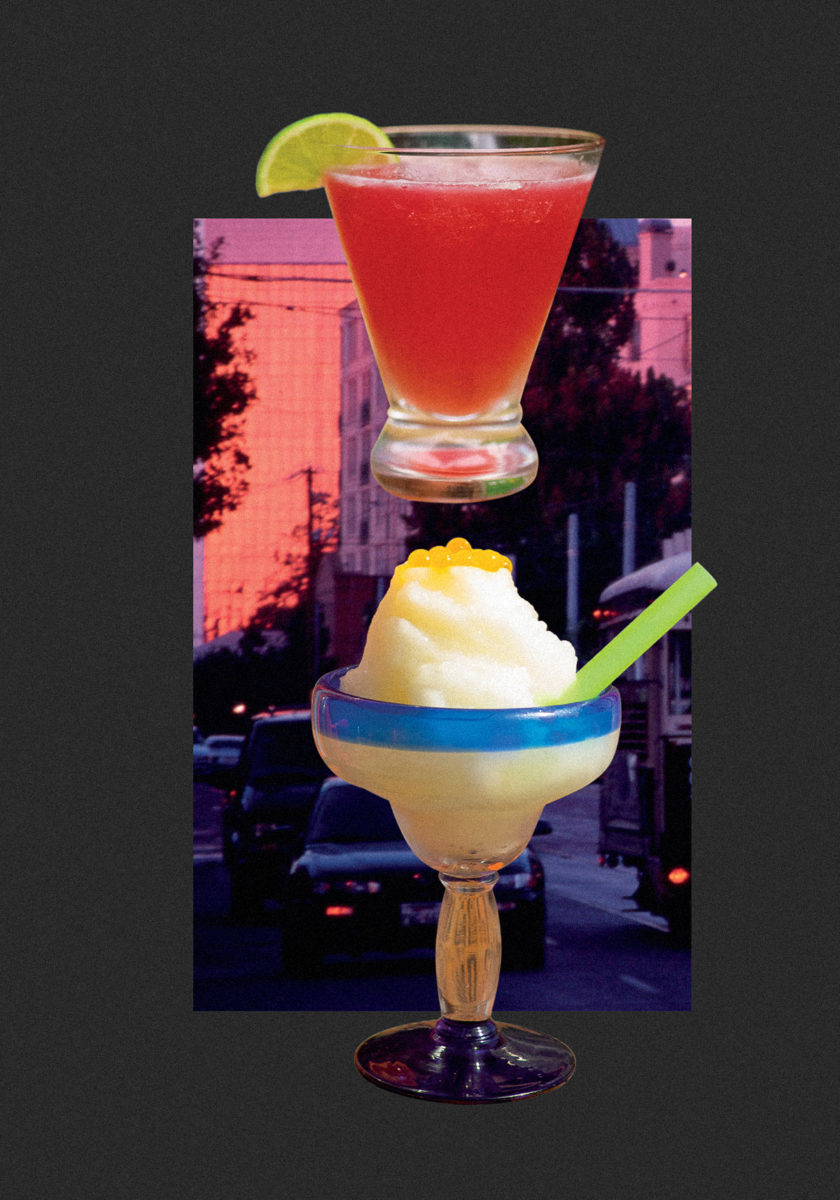

For Chef Rodarte’s part, his family-run Beto & Son menu has reimagined Mexican classics with stacked (instead of rolled) enchiladas and carnitas noodle bowls, though the real star of your meal here will be the Nitrogen Margarita. It would be easy to dismiss this potent drink as mere Instagram bait, but the Beto & Son invention, sparked after Rodarte’s education at the American Culinary Institute, is the new platonic ideal of frozen margaritas. By freezing the pure ingredients of a margarita, the nitrogen creates a perfect drinking experience: No melted ice slush; no watered-down flavor. Just try not to get a brain freeze.

The best hotels and neighborhoods to stay in Dallas, Texas.→

The Nitrogen Margarita is emblematic of an answer to the question I kept asking myself: If Dallas is expanding its palate and evolving its culinary identity in line with trends that have taken hold across the nation—more inventive and diverse cuisine, casual dining environments—what makes the Dallas dining scene still feel like Dallas?

It all goes back to “getting Dallas ready.” Everything really is bigger here—sometimes this literally means the portions, but usually it means personality, even in tiny outposts like YaYa Best Tex Mex Yogurt in the Bishop Arts District. Quirky art from the personal collection of the owner, a former commercial real estate developer turned artisanal fro-yo master, lines the walls where patrons are invited to mix flavors like Gentle Jalapeño and Homemade Horchata, both of which are trademarked. In the same neighborhood, you’ll find Salaryman, a Japanese-Texan izakaya spot, and Lucia, a cozy, creative Italo-Texan restaurant using local ingredients. There’s also Good Companions, a natural wine bar and scratch-made pastry shop, and The Wild Detectives, a bookstore bar/cafe serving locally sourced snacks like breakfast tacos and tostas.

“What makes the Dallas dining scene still feel like Dallas?”

On the nightlife side of things, you’ll also find exquisite dives like Lee Harvey’s (named for the infamous slice of Dallas’s presidential history), which serves absolutely perfect onion rings that pair well with live music and a local beer. Or try Cosmo’s in Lower Greenville, which serves up retro ’70s vibes, solid drinks, and stellar late-night Vietnamese food, complete with jukebox and VHS player. You’ll also want to down a YooHoo YeeHaw at Double Wide, which rivals Beto & Son in the frozen-drink genre—add string lights, live music, and toilets repurposed for outdoor seating and you’ll stick around the Deep Ellum mainstay all night long. (Also make note of Lizard Lounge across the neighborhood, which hosts a Satanist church on Sundays.)

“My restaurants were always really well designed and furnished, and it was a whole experience,” says Pyles. “The places I go today that have really good food, I’m just like, ‘Good lord, did you spend anything on this place?’ And that’s cool that they don’t have to—it’s a different kind of experience.”

It seems that Dallas chefs and restaurant owners have created something all their own in this new era of dining—something without stars, sure, but with something more important: substance.

The stories for Here Magazine issue 12 were commissioned well before the World Health Organization declared the COVID-19 crisis a global pandemic. We hope these stories bring the world a little closer to you—and offer some reflection on the world we want to return to once it’s safe to travel again. To learn how you can help affected communities around the world, visit GlobalGiving’s Coronavirus Relief Fund.