Hotelier Damon Lawrence’s hospitality brand, Stay Homage, offers Black clientele a thoughtfully curated travel experience informed by Black history and culture.

A few years ago, in response to a study revealing that Black Americans actually sleep less than other races, Oakland-based artists Ellen Sebastian Chang and Amara Tabor-Smith created a series of performances “evoking the right of Black women to have rest.” For a week, silent processions of veiled women dressed in white paraded through the streets of Oakland, carrying parasols and lanterns, before gathering in cosy, artist-designed spaces to sleep and record their dreams. I remember being awed by how “Black Women Dreaming” had revolutionized such a basic, simple need.

It was a feeling I recently revisited while speaking to Damon Lawrence, founder and CEO of Stay Homage, an award-winning boutique hotel brand that pays homage to Black culture and acknowledges the need to rest. In their goal to make guests feel “reimagined, visible and welcome,” Lawrence and co-founders Chimene Jackson and Kearra Taylor are taking a thoughtful look at both history and recent events and asking, what do Black folks truly need in order to rest and recover? This question shapes their innovative business model, strong community outreach, and art and music-driven design and programming. The result, which they’ve tagged “a new kind of hospitality,” is right on time.

The company’s origin story is itself an example of Black resilience. In 2014, as Lawrence, a veteran of the hospitality industry, was pondering why hoteliers didn’t look like him, his father made him sit down and watch Fruitvale Station, the movie about Oakland native Oscar Grant being shot by transit police on New Year’s Day. Then in April 2015, 50-year-old Walter Scott was shot by North Carolina police during a routine traffic stop. “With him,” Lawrence explains, “I saw my father, my uncles, my grandfather, my elders. That was harder to stomach.” Three months later Sandra Bland was found hanged in a Texas jail cell after being arrested for an alleged traffic violation. “I saw my sisters, my mom. How do you protest against that?” Seeking an answer and channeling his pain, Lawrence quit his job and set up shop in his mother’s house. He would fall asleep at his computer, wake up, eat the dinner his mother had brought him, shower, and start back in. Working on a business plan “gave me something positive to focus on. How does your work become your voice?”

He knew he had to do business differently. Lawrence and his partner at the time didn’t have nearly the same access to funding that white teams did; in fact, Black entrepreneurs receive less than one percent of all U.S. venture capital funding. With a small amount of investor and family capital, they were able to purchase and renovate a four-room property in New Orleans, a city with a long history of Black resilience and innovation—as well as exploitation by the tourism industry. Stay Homage took care, and took its time, to build relationships with the local community. The team conducted countless oral histories with neighborhood residents and local historians “to get the true story you don’t get through Google.” The subsequent archive of audio and video recordings informed design decisions that paid homage to a rich history that begins long before the antebellum era New Orleans normally markets and included the legacies of Mardi Gras Indians and the huge population of free Blacks.

The Here Magazine Guide to New Orleans, Louisiana →

Customers arrived at The Moor to find themselves amidst art by local artists including BMike and The Artist Jade, with Ella Fitzgerald and Louis Armstrong playing in the lobby. The welcome design signaled that a mindful journey had begun and highlighted the importance of music culture to New Orleans and to Lawrence himself. His mother was a talented backup singer who played music according to time and mood (“Mom’s Sunday playlist meant it was time to clean up…”), and he grew up around music, inspired by its relationship to place and space. “You can change the entire environment of a location by what music you play,” he says. The company’s values statement are actually song lyrics from musicians like Nina Simone, André Benjamin, Lauren Hill, and Kendrick Lamar. For inside the rooms, Lawrence tracked down copies of the special Katrina issue of Black Scholar Journal to place on each nightstand. Touches like African textiles, Shea butter lotion, and iconic African Black soap showed how “we put thought and intention around giving people rest.” Guests raved about how at home they felt. “They don’t understand that typically, they do not,” says Lawrence. “You’ve borne it for so long you don’t even realize.”

In 2019, up against bigger, richer companies, The Moor won such awards as Boutique Design’s “Up and Coming Hotelier of the Year.” Homage partnered with Essence Fest, and bookings were strong. Then COVID-19 struck. Across the nation, nearly half of Black-owned businesses closed their doors—compared to just 17 percent of white-owned businesses—and The Moor shuttered. And then George Floyd was murdered. Lawrence leaned hard into his original inspiration, writing on the company’s blog, I need Homage to exist not as an entrepreneur or owner but as a consumer. Black people need rest too y’all. We’re tired. Rest is both a psychic concept and a political reality for Black Americans, who have always traveled but have not always been welcome. The challenge of finding safe, welcoming places to stay was famously addressed in The Negro Motorist Green Book, the iconic mid-20th century guidebook. Harlem-based author, photographer and cultural documentarian Candacy Taylor, whose work documents and preserves Green Book sites, notes the irony that, with legal desegregation, many such havens have been lost.

In 2019, prior to COVID, Black leisure travelers spent $109.4 billion on U.S. travel, choosing destinations based on perceived safety for Black travelers, as well as the location’s diversity and representation. Homage was trying to do its part. Lawrence had spent the last five years living in Oakland, California, a formerly Black city hard hit by gentrification and a housing crisis. He had amassed an impressive array of creative partners, including the community celebration known as Black Joy Parade; artisanal, direct trade coffee empire Red Bay Coffee; and Chef Nelson German of Top Chef’s Season 18. He had moved into a hotel site and was ready to start renovations. As construction across the country shut down, he watched the unsheltered community outside his doors explode. “Meanwhile I’m camped out in an empty, 92-key property. It felt extremely irresponsible,” he says. In an unprecedented move, he leased the space to the city for transitional housing. Lawrence views the setback as an opportunity to understand community needs, and says he learned more than if the hotel project had proceeded smoothly. “Ultimately it will make me better. Even once this is a hotel, how can we continue to help people who don’t have a place to stay, who aren’t finding rest?”

The Survival of New Orleans’s Arts Community After Katrina →

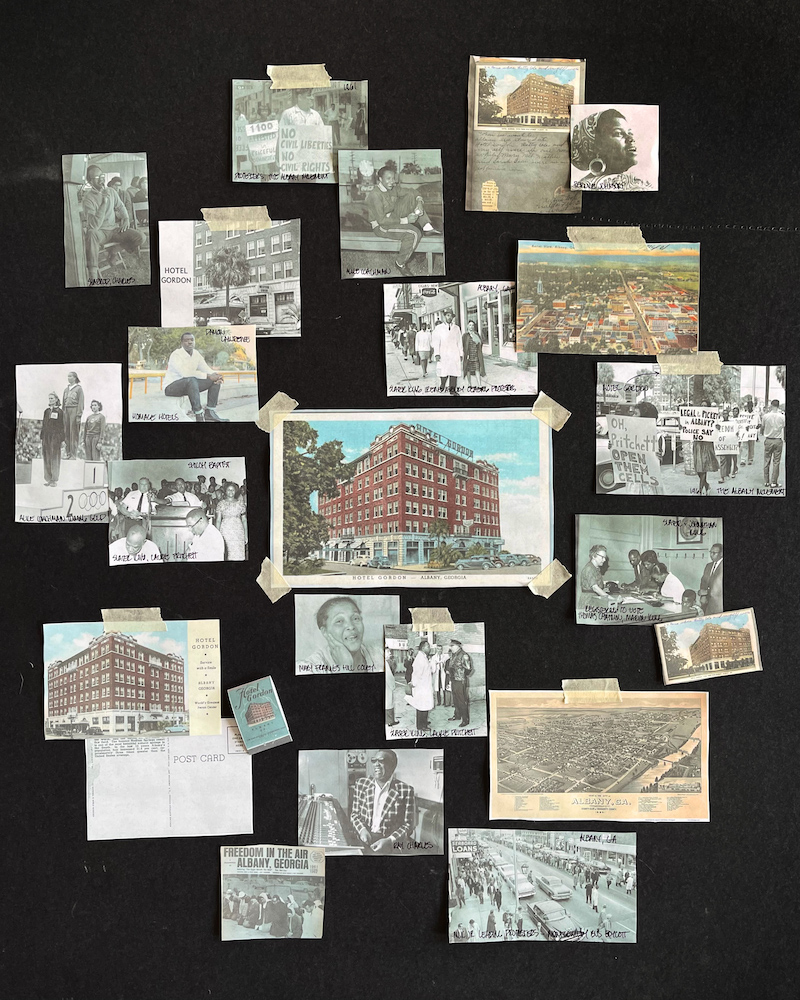

The enforced lockdown provided additional opportunities to recalibrate. Homage’s model of choosing neighborhoods and cities that have “untold stories” means spending extended time in a single market to understand its history and culture. This month, Lawrence is moving to Albany in southwest Georgia to prepare the next property, under the advisement of Peter Cole, former CEO of Design Hotels, a global network of independent, design-driven hotels that function as social hubs. Albany is a picturesque, predominantly Black city that was long inhabited by the Chewhaw people and was significant in the Civil Rights movement. Once the third largest city in the state, it has one of the highest out-migration rates in the country, and despite being surrounded by farmland, is a food desert. Making it a travel destination is both a challenge and an opportunity. Lawrence is working with a famous restaurateur (who is yet to be named publicly) and will spend six months exploring partnerships with local farmers, artists, makers, and creatives to create a full experience on the same street as the hotel, as well as “meaningful day trips that give back to the community in a real way.”

Homage is now raising both real estate and venture capital and has plans to expand into Baltimore, Charlotte, Chicago, Dallas, Harlem, Los Angeles, Memphis, Philadelphia, and St. Louis. The prospect of someday being able to cross the country staying solely in Stay Homage properties feels like our ancestors’ wildest Green Book dream. As Lawrence puts it, “Travel is a basic necessity, a basic human need, just like human interaction. There’s no replacement for sitting across from someone and looking them in their eyes. We had that taken away for a period and we’re just getting it back. Now we need to prioritize the reasons we travel. What are we doing for each other? What are we giving back?”