In this series, we’re highlighting the stories of people who remain connected to their home countries—either those with immigrant parents or those who are immigrants themselves. With “We Are All Immigrants: Stories About the Places We’re From,” you’ll hear from those most acutely affected by changing policies and a shifting reality, those who exist as part of multiple cultures at once. Here, London-based professor and writer Emma Dabiri explores what being an immigrant means to her and to her family.

I am an immigrant. However, despite the cultural dislocation and confusion this identity can incur, I actively chose to become one in part to escape the racism that many immigrants only experience after they leave home.

And although my parents were born and raised in countries not their own, I’m not sure that the term immigrant applies to them in the way it does to me.

I was born in Dublin and have lived in London for almost 20 years—since I finished school—which quite straightforwardly makes me an Irish immigrant. Ostensibly I am Irish, but when the inevitable “Where do you come from?” is asked, that answer, rarely, if ever, satisfies people. Race, it would appear, complicates things.

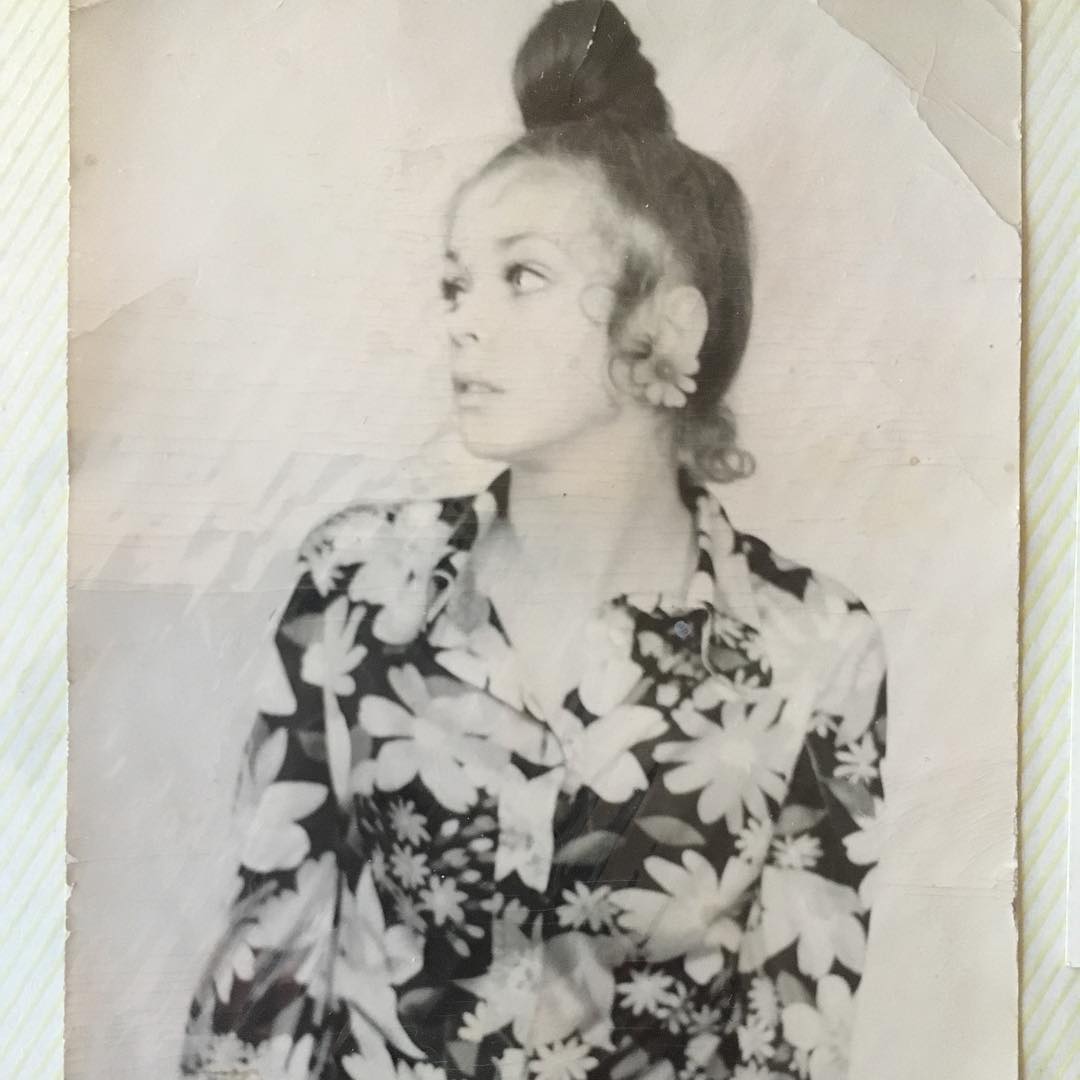

My mother is Irish, too, but my Irishness is always contested in a way that hers never is. This is interesting, because my Irish mum was actually born in the Caribbean (to Irish parents) in the 1950s. She lived in Trinidad until she was 15 or 16, at which point she returned to Ireland. However, with her white skin and Atlantic-blue eyes, people find her description of herself as Irish completely unremarkable. Unlike mine.

With her white skin and Atlantic-blue eyes, people find her description of herself as Irish completely unremarkable. Unlike mine.

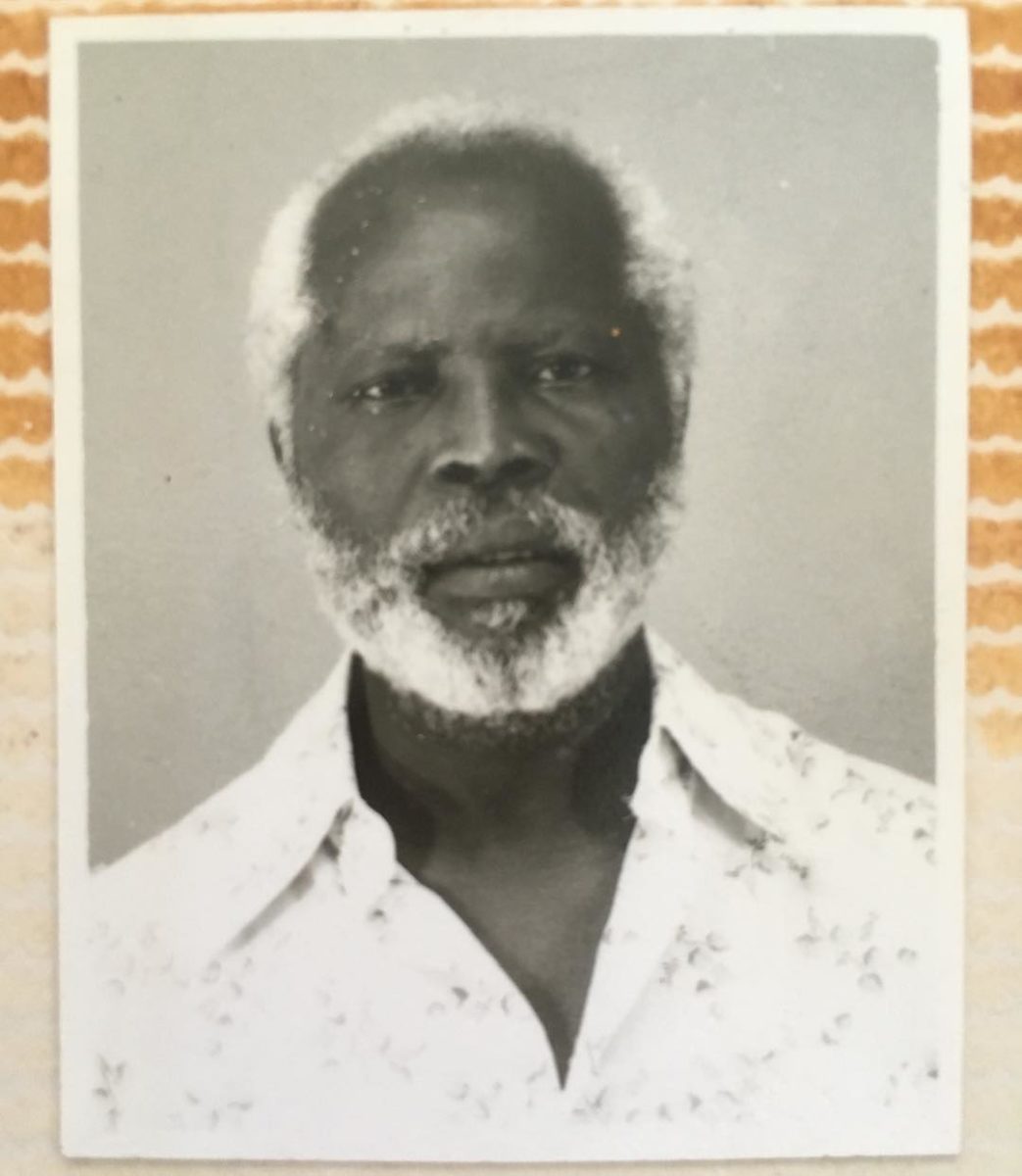

My father is Nigerian—he came to Ireland as a student in the 1970s—but again beyond this, his background is atypical. His Nigerian parents were in Ireland in the 1940s and 1950s while his father completed his studies in Trinity College. My Nigerian aunts and uncles were all born in Ireland, and my dad went to primary school in Rathgar in Dublin.

Yet despite these cross continental movements, I’m not sure that either side of my family are immigrants in the true sense of the world. They had no intention of staying in the countries they found themselves in. They were always going “home.”

My Nigerian family returned to Nigeria upon my grandfather’s graduation, as planned. My Irish grandfather was in Trinidad, but was never seeking to become Trinidadian. Trinidad was a British colony and he worked for the British government. At the time my paternal grandparents left Nigeria, it was still a British colony. My grandfather “made it,” attaining the holy grail of university in Britain (he originally went to Edinburgh, but having found it too dry, transferred to Trinity because he had heard that Dublin was supposedly home to a vibrant Nigerian student community in the 1950s. Still trying to get my head around that one). Upon graduating he returned to Nigeria where he set up a law practice in Jos handling cases such as the defense of black miners protesting against the discriminatory practices of the British colonial authorities.

Likewise, my maternal grandfather from Ireland had “made it,” too, when he got into Cambridge in the 1940s. The scope of adventure that was now opened to him as part of the empire on which “the sun never set” ushered in a world of glamorous possibility for him, far beyond the opportunities of the poverty stricken rural West coast of Ireland. The colonized as colonizer. Rarely a worse combination.

But it is this—British colonialism—that remains the connecting yet invisible thread that links these seemingly disparate genealogies.

For so many of us, home is a nebulous concept. I miss Ireland, but could I live there?

These cross-cultural migrations set the scene for my birth. Yet unlike either of my parents, I physically embodied all of that mixing, and my reality was very different from the international upbringings of my parents. I grew up with a single mum in a very white, very underprivileged part of inner city Dublin. While have a deep connection to Ireland and love being Irish, my childhood there was not easy. I knew as soon as I finished school I would leave, which is exactly what I did, like millions of other Irish who left the land of their birth permanently to seek a better life across the sea. Yet, it was unalike, too. These other Irish people left home and discovered a version of the discrimination I was fleeing. Although we are both Irish, they would have to leave home to experience racism. I had to leave home to escape it. And yet I know this idea of escaping racism is an illusion. The UK is inarguably racist on an institutional level, but living here has at least given me the opportunity to find a community of others who experience the world in a similar way to me. It has given me breathing space, where I am no longer defined as “the black girl”—an exhausting existence—but rather, there are other black women around me.

Is it full circle that I find myself in the UK, the very country whose machinations set in motion the wheels of migration responsible for the fractured, diasporic journey of my family. Both Ireland and Nigeria share a recent history of being colonized by the British, with all the attendant consequences, in terms of nationhood, economy, and identity.

For so many of us, home is a nebulous concept. I don’t know that I can locate it with any geographic specificity. I miss Ireland a lot, but could I live there? I don’t know. It’s changed a lot since I left, there are many more black people, and I know that my alterity would feel less pronounced.

I recently went to Barbados for the first time. A Bajan casually asked me if I was home on holiday. I burst out laughing. This was something I had never been asked in all my years going back to Ireland. It was such a novel feeling—to be claimed, to belong. Even momentarily. Even when I didn’t.