Fifteen years after Hurricane Katrina, some areas of New Orleans remain abandoned, while others are bursting with tourists. As the community grapples with both, local artists—themselves a mix of natives and new arrivals—work to make it in the city that inspires them.

As a writer who’s lived in New York for eight years, it’s easy to romanticize smaller American cities. I imagine what a slower pace would do for my output; how less time commuting each day would mean more time for creating or just thinking.

New Orleans has always lured people with unbeatable nightlife, fried food, and debaucherous Mardi Gras parades. But I’m more interested in the city’s creative class, and why artists seem attracted to New Orleans like flies to sticky-rimmed cocktails. “America has only three cities: New York, San Francisco, and New Orleans,” writer Tennessee Williams once allegedly said. “Everywhere else is Cleveland.”

Don’t get me wrong: When I visited the city at the start of Mardi Gras earlier this year, I certainly participated in all the usual rites and rituals of the season. I drank Sazeracs from go cups, listened to live jazz at the Ace Hotel, and watched the infamous Krewe du Vieux parade. But during my trip I also attempted to uncover exactly what makes New Orleans so alluring to artists today.

Unwittingly, the pulse of all my interviews was the same: 15 years after Hurricane Katrina made landfall in New Orleans, damaging over 200,000 homes and displacing over 800,000 people, the storm remains a regular topic of conversation. Lyft drivers taking me from the city’s Central Business District to the Bywater would point to areas that had been underwater. People I spoke with told me Katrina was the reason they “found themselves” in New Orleans—whether literally or figuratively, as newcomers or returning residents.

6 Artists Uplifting Community Spirit in New Orleans→

The artist Brandan Odums, who goes by BMike, calls the storm a “bookmark” for the city: “It’s a way we gauge time now,” he says. “If you reference anything, the response is, ‘Before or after Katrina?’”

I learned that the storm left a vacuum of cheap rent, creating opportunity for outside artists as well as buyers looking to invest in short-term rental properties. At once in need of and at odds with each other, both of these groups have shaped the city in the years since the storm, and not always for the better.

Painter Ida Floreak was one of the “transplants” that moved to New Orleans during this period. “[In 2011,] it was post-Katrina but it was also right after the [financial] crash. It seemed like the only options at the time were San Francisco and New York, and those places were so prohibitively expensive,” she says. “All the friends I saw [there] were working three jobs and miserable.” New Orleans, however, seemed like “a city where it’s a little easier to scrape by because it’s just cheaper, but there’s also a social openness.”

Floreak’s work presents objects found in the natural world (an egg, a cicada, feathers) as religious deities, combining surrealism and anthropology to dramatic effect. “The aesthetic of my work is definitely shaped by the city,” says Floreak.

For Floreak, creating art without needing to sell it is essential. And while there isn’t much of a market around art in New Orleans—let alone much state funding for it—she feels there’s a lack of commercial drive that makes the city more hospitable to artists. “There’s not a judgment around not having it together. In other places there’s a striving to look like you’re doing well that can be pretty damaging,” says Floreak. “Because if you’re striving to make money you’re not going to make good, honest work.”

A Travel Photographer Captures the Vibrant Colors of New Orleans→

It’s a familiar cycle: A city’s financial struggles make it attractive to artists who make it attractive to tourists and the predatory institutions that sometimes come with tourism, like gentrification. In Detroit and Lisbon, cheap rent is the culprit behind what many see as an “artist revival,” in spite of decaying infrastructure and political corruption. And because young creators are often looking to work together, cities that are less competitive and more open-minded hold a lot of appeal. “New Orleans is just such a welcoming city in which there’s no dumb idea. Anything is possible if you can get a group of friends to rally around it with a case of beer,” say the founders of DNO (originally Defend New Orleans), who prefer not to be named. “There’s enough time and space to support other people’s projects.”

DNO was founded by New Orleans natives in 2003 as a screen-printing and T-shirt business. “Defend New Orleans” was initially a campaign meant to “stop New Orleans from becoming like anywhere else.” “It was just this abstract cultural statement,” the founders tell me from the backyard of their namesake store on First Street. We’re under a wooden awning in case it starts raining, and there are cigarette butts scattered around. You get the sense that lots of conversations about new projects have happened here. After Katrina, the whole ethos of DNO changed. “It was like, this could all be gone. When it comes to people who lived here pre-Katrina, defending New Orleans has this face of: we almost lost it, and we really worked hard to get it back.”

The Ultimate Road Trip from Austin to New Orleans→

It seems nearly impossible to be an artist in New Orleans and not feel both devastated and inspired by Katrina. BMike was particularly reenergized, creating video work that spoke to the changing sociopolitical landscape. “We felt the mainstream media wasn’t really reflecting what we saw and what we knew was happening. And so I think the creative community helped, as it always has.”

Now, BMike works mostly in graffiti, creating a series of public artworks which have culminated in Studio Be, his 36,000-square-foot gallery featuring large-scale murals and room-size installations. The day I met up with BMike, the studio was closed (it’s only open four days a week), but he let me walk through the cavernous space. I paused at an installation resembling half a basketball court, with the words “The ball should bounce the same for everyone” and “1/3 black males will go to prison in their lifetime. 3/10,000 will go to the NBA” spray painted onto surrounding walls and panels.

“When you think about it, even before Katrina, there has always been a narrative of bad and a narrative of pain,” he says. “You can go all the way back to when the French Quarter was one of the biggest auction areas of black bodies and think about how that was happening at the same time as incredible genius through music. So there’s always been this balance of ugliness and beauty or survival and defeat. I think that dynamic in this city has always been such an interesting glue.”

In the 15 years since Katrina, the population has been replenished and then some—though resources have not been equally distributed. A recent study by Urban Studies Journal shows that natural disasters are actually a precursor to gentrification, citing individuals, developers, and policymakers who take advantage of lower housing prices. The study states that gentrification “is often associated at least in the public’s mind with an influx of young, white and educated homeowners, and the specialty cafes, bars and restaurants that serve the new residents.”

“People are very, very sensitive to these issues,” says Floreak. “I’m trying to frame it in a way that doesn’t sound…” she trails off, before stating the real crux of the issue. “I’m privileged, and came in as an educated white person in a city that’s largely black and poor.”

Artist and Performer Big Freedia’s Guide to New Orleans→

As such, rents are no longer as affordable as they once were, because of gentrification as well as the influx of tourists to New Orleans, who are driving up the number of short-term apartment rentals (and, as with operations like Airbnb, sometimes driving out residents). “It’s an exciting place to be, but it’s rapidly evolving and changing,” says Rosalie Smith, artist and cofounder of the Lucky Art Fair, a Mid-City event that had its first run in June. “The entire city feels very much under threat because of the way Airbnb has developed—it’s threatening us as much as an impending natural disaster.”

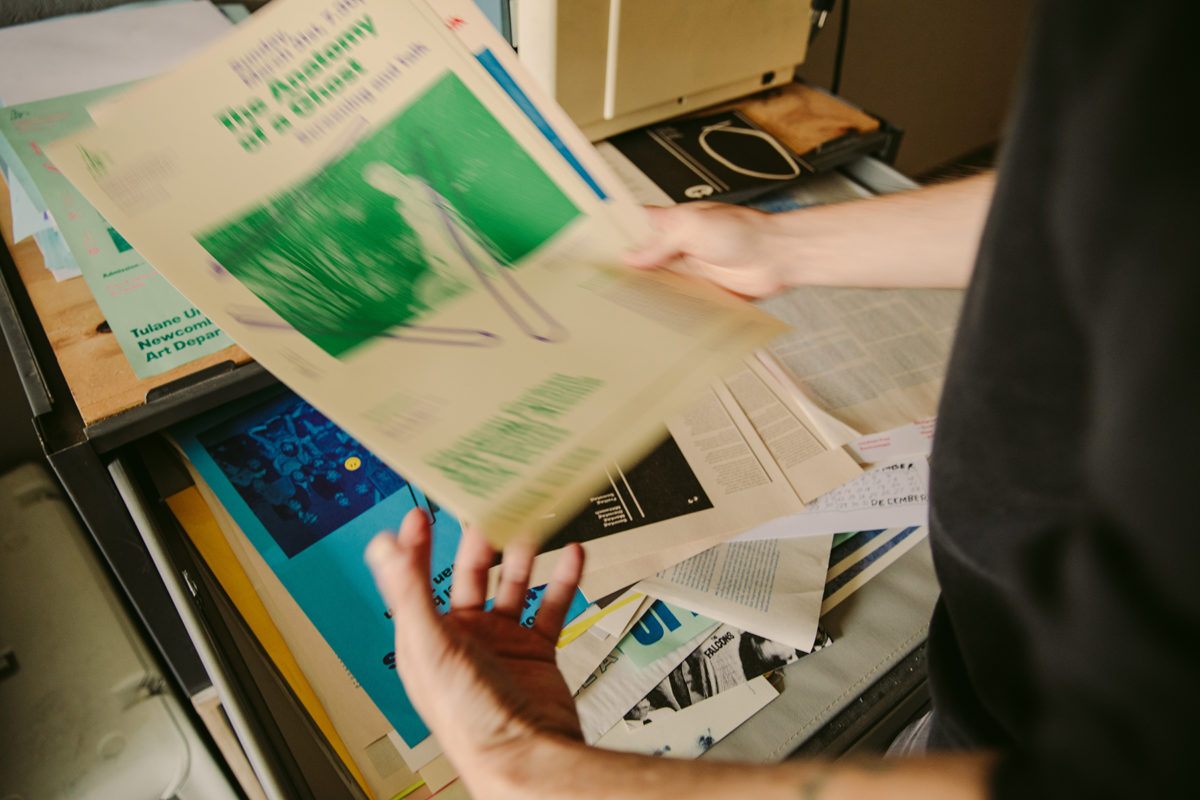

Neighborhoods like Tremé and the French Quarter used to be prime ground for artists, who are now being pushed out to surrounding areas like Arabi, where there are a growing number of studios. Erik Kiesewetter, the founder of printing shop constance, works out of a space just “three buildings down from the Mississippi.”

Inside Kiesewetter’s second-floor studio are two jaunty risograph printers and various Mardi Gras posters in acid-wash colors. constance was another product of Katrina; in 2005, Kiesewetter put up flyers around town as an open call for writers, painters, photographers, graffiti artists, and graphic designers to contribute responses to the storm. The result was a 1,000-book run of a literary arts journal that gave voice to those affected by Katrina and its aftermath. Since then, Kiesewetter has published an arts blog and created an online arts critique platform, among other things. Currently, his business is mainly printing and design.

In New Orleans, today’s threats may be different than those in 2005, but the impulse to band together as a community remains.

For BMike, that means making sure a new class of artists is being cultivated from within. “I’m thinking about how to make sure that a story like Studio Be or a story like mine isn’t restricted to just me,” he says. “I can be an example to younger artists, and show them that there is a path that they could take that is sustainable.”

Smith’s inaugural Lucky Art Fair is another example of rethinking the infrastructure that supports artists: She paid each participant an even share of the overall fair profits. “It’s a little bit of a socialist financial structure, but it’s based on the belief that all art is equally valid and worth being paid for.”

Even as rents and tourism rise, the city continues to be what inspires Smith. She creates pieces that speak to “the temporality of life,” including work that uses synthetic flowers collected from drainage channels of New Orleans cemeteries after Mardi Gras parades. “The artificial flowers struck me as so poignant and beautiful because it’s a gesture of love that will last forever,” Smith says. “Ironically, the synthetic materials they’re made of are what perpetuate the wild weather patterns. So they’re beautiful, but they’re mournful and sad in a way too. And there’s something about life here that’s sort of about that as well.”