When an airplane crosses over the invisible line that demarcates the beginning of Hawaii, flight attendants pass out agriculture declaration forms so that passengers can indicate if they’ve packed any invasive species in their carry-ons. Under “Reasons for this trip,” the first option on the sheet is “Honeymoon.” The second is “To get married.” But I didn’t need a printed list to know that those were the top two reasons most people on my flight were traveling to Hawaii.

All around me, husbands nuzzled their new wives. One woman wore a white T-shirt with the words “Honeymoon Vibes” printed in gold lettering across the front; it went with her new jewelry and the remnants of her French manicure. Admittedly, I was more attuned than normal to the coupling of my fellow passengers (I could practically see Instagram’s “like” icon above each pair of seats). For I was en route to the honeymoon capital of the world by myself, having just ended a major relationship—and no amount of Hawaiian Airlines’ entertainment was going to help me forget it.

It didn’t help that my ex seemed to follow me everywhere—his name startled me when I saw the familiar letters on a flight attendant’s name tag, and again when it appeared not 10 pages into my book. Then there were the small, dumb moments when I felt most single, like when I had no one to call on my layover between Honolulu and Hilo, just to say, “Hey, I’m alive,” or “A baby screamed for literally the entire eleven-hour flight.” Instead, I texted my mom and ate at Stinger Ray’s, where I was tempted to order something frozen and alcoholic, but didn’t because I had to pick up a rental car on the other side of my 45-minute flight. Already, I felt a little bit like how I’d felt at summer camp growing up: I wanted to be there (or at least, I wanted to want to be there), but I was also counting down the days until I could go home.

But, this trip, I had an agenda. My plan was to escape the intensely emotional with the intensely physical, and I had compiled an itinerary full of adventurous activities that wouldn’t leave room for mental breakdowns: waterfall rappelling, solo hikes, and negative temperatures on top of the Maunakea volcano. If I couldn’t get out of my head, I would at least get into my body. This was my own version of wellness travel—one week of serious alone time, surrounded by Mother Nature’s beauty, to remind myself that I am capable and that things would be okay. I could have checked myself into a weeklong yoga retreat, full of lithe New York bodies, vegan fare, and an infinity pool, but I felt this approach would somehow be much more effective.

I arrived in Hilo after dark and made my way to the Old Hawaiian Bed and Breakfast. My accomodation was a proper B&B (without the “Air-”; remember those?), on the ground floor of an actual home, and before I retired to my room my host told me she would pack breakfast for me, since I had an early start. It wasn’t a five-star yoga retreat, but there was something deeply restorative about that personal care.

I woke up early the next morning and stepped out into the lush backyard, all misty gray and vibrant green. At Kulaniapia Falls I met Ethan and Jeremy, who run waterfall rappelling for Kulaniapia Adventures. It’s usually a group activity, but this morning it was just me, and thank goodness—it took me more than two hours to make it down the 60-foot practice “bunny hill,” followed by the 120-foot falls. If one were searching for a metaphor for breakups, rappelling down a giant, jagged, slippery façade offers a lot to work with. Getting over the ledge is by far the worst part; losing your footing and crashing halfway down is panic-inducing for a moment, until you realize you’re actually fine, save for a scraped elbow; and you eventually arrive at the bottom, shaking but on solid ground.

Conquering a fear of heights is much easier than dining alone. Moon & Turtle, the farm-and-sea-to-table restaurant from Mark and Soni Pomaski, is unassuming, delicious, and chock- full of duos celebrating anniversaries, birthdays, or the birth of their first grandchild. The restaurant very nicely serves complimentary sparkling wine to anyone commemorating an occasion. I’m not exaggerating when I say that mine was the only table without gratis bubbly. My job requires a decent amount of solo travel, which is usually a pleasant break from New York’s social demands and life’s routine. But on this trip, I was not just alone, I was also lonely. Nevertheless, I channeled my inner independent woman and ordered myself multiple glasses of rosé, which I enjoyed alongside smoky sashimi and fish fried rice.

When you’re asleep by 8:30 p.m., you’re practically guaranteed to be one of the first people awake and driving into Hawaii Volcanoes National Park in the morning. On my visit, I was one of only a handful of people at the Jaggar Museum Overlook, where lava was clearly visible inside the Kilauea caldera. The Kilauea volcano erupted shortly after my trip, and had been flowing lava since, destroying nearby homes. Standing there, I could hear the lava; it sounded like crashing waves. “That’s Pele talking to you,” said Jessica Ferracane, PR director at the park, over lunch, referring to the Hawaiian goddess of volcanoes. What was she saying?, I wondered. Hopefully something like, “You are brave and strong and are going to be just fine.”

Hawaii seems to be full of brave women who are facing the elements—of both nature and life. Take Ka’iulani Murphy, a navigator on the Mālama Honua Worldwide Voyage, a three-year journey through 150 ports and 23 countries on a traditional Polynesian double-hulled canoe with no modern instruments. Murphy, along with 245 other crew members, uses traditional wayfinding methods—the sky and stars are her map. “Observing signs in nature to find our way has taught me so much, especially that I’ll always have more to learn,” Murphy says. “Our navigation process, or wayfinding, depends on our understanding signs in nature. You really need to develop a relationship with nature to understand how to read its processes.”

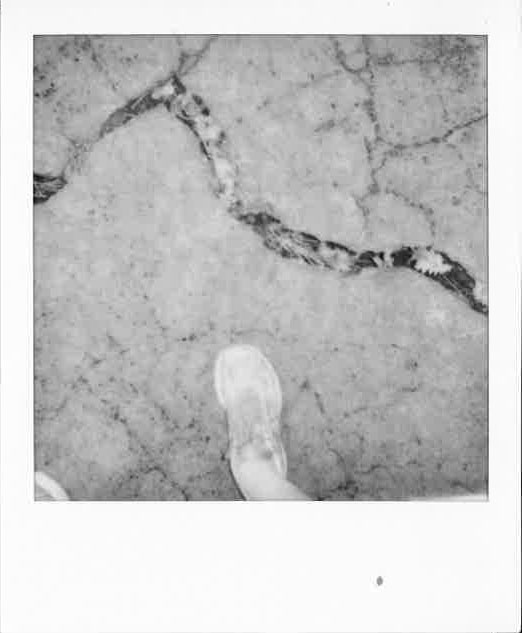

There are many ways to process a breakup, and connecting with nature was my recovery method of choice. I hiked the Kilauea Iki trail, down through rainforest terrain and into an expansive crater, where the rock floor rippled and bulged upward, frozen in time after its last explosion in 1959. On the downward climb, I thought about my relationship, and about how a relationship built on unsolid ground will burn bright and fast, destroying everything in its path, not unlike lava. It wasn’t until the next day, when I was face-down on the massage table at the Four Seasons Resort Hualalai, a blend of salts meant to awaken my seven chakras being applied vigorously all over my sunburned body, that I had the kind of awakening I’d come to Hawaii for: Maybe there’s no man at all. Or at least, maybe what I’m looking for isn’t inside a partner but within me, buried deep after nearly a decade of back-to-back relationships.

I was thinking about all this—a me that’s not in relation to someone else—as I flew over the Pu’u Ō’ō crater with Paradise Helicopter Tours. By road you can only see about 20 percent of Hawaii’s landscape; by air, you gaze out over the other 80 percent and all of the island’s 10 climate zones in three hours. We skimmed over window panes of lava called skylights, green valleys, and waterfalls as tall as buildings. We passed over the mega resorts in Kona, where the turquoise- colored ocean is marred only by the dark patches of pristine reef. We soared over everything—9,000 feet at our highest point—and suddenly the sensation of being above it all was as true literally as it had been figuratively.

Martha Cheng is a writer who moved to Hawaii with her husband, then fell in love with surfing and left him for it. For Cheng, the water is like a relationship— imperfect but constant. “There’s something special about surfing; every time you go out there’s no guarantee that you’re going to catch a wave, because you can’t control anything. It’s a lot like the slot machines in Vegas—sometimes you win, sometimes you don’t, but when you do, it feels amazing. So you just keep pushing that lever.” Sounds an awful lot like dating, too. Along with surfing, Cheng has completed the Molokai-to-Oahu crossing, a 32-mile paddleboard course, which she’s done “prone,” or without the use of paddles. She’s currently taking freediving lessons, which is scuba diving without the gear. I tell her I sense a pattern in her extracurricular activities, and she laughs. “I guess I’d never really been the sporty person, so I wanted to prove that I could be,” she says. And it turns out, it’s mostly mental anyway. “My instructor told me, ‘You have enough oxygen to hold your breath for three minutes, but your body’s freaking out, it’s telling you to breathe, it’s in pain, and you need to push past all that,’” she says. “I asked him, ‘Aren’t there any physical techniques that you need to teach us to be better divers?’ And he told me, ‘Yeah, but that doesn’t come until years after you get past the psychological blocks.’”

Humans are very good at letting their emotions—especially fear or sadness—override their biomechanisms. Pushing yourself physically is one way to combat that. My call time was 2 a.m. the next morning to reach the top of Maunakea, a dormant volcano, by sunrise. Hawaii Forest & Trail drove me and 20 or so other passengers up 10,000 feet, where we stopped to acclimate, drink coffee, and stargaze. Scorpio was visible just below the moon, which felt significant; I follow plenty of astrology accounts on Instagram, but I’d never seen my sign in the wild. A few hours later, from above the cloud line, we watched orange, yellow, and purple paint strokes light the sky. It felt like we were on top of the earth, or maybe at the end of it. Either way: perspective. (It also felt like -5 degrees with the windchill.)

My island tour culminated in Waimea, where I putzed around my room at the Kamuela Inn, diving into e-mails and writing. I couldn’t really bring myself to explore beyond my pre-scheduled activities. The rhythm of my life in New York was pulling me again—I felt…homesick? After 4,899 miles by plane, 200 miles by helicopter, 14 meals alone, 120 feet of waterfall rappelling, 4 miles of hiking, and 13,802 feet of summit-ascending, I was ready to go home—a home without a boyfriend or a dog, or anything except myself and a clean slate.

I ate my final solo meal at Merriman’s, a white-tablecloth restaurant where I counted at least two birthday cakes coming out of the kitchen—another celebration destination. There were couples, families, friends, and me—alone but not lonely, with my macadamia-nut-crusted kampachi. The table next to mine sent me a glass of wine. I gave a silent cheers to myself and drank up the gratitude.