Why the street protest is the most important kind of road travel in 2020.

On a two-block stretch of pavement leading up to the White House in Washington, D.C., the words “Black Lives Matter” are etched in 35-foot-tall, bright yellow letters. Two nearby street signs bordering the statement announce that this is Black Lives Matter Plaza. Since June, the plaza has become a daily gathering place for everything from rallies and marches to dance parties and cookouts. It’s seen both peaceful protests and violent conflict between local police and demonstrators, including when police forcibly removed a crowd of peaceful protesters to make way for President Donald Trump’s photo op in front of St. John’s Church.

Across the country, similar messaging has popped up on streets from Raleigh, North Carolina, to Sacramento, California, and beyond. It’s all part of a racial reckoning that is taking place amid a deadly pandemic that shut down thousands of destinations. This summer, it’s likely that cross-country road trippers would have found more places to stop and protest than to buy touristy merchandise.

Between May 26—the day after George Floyd was killed by police in Minneapolis—and August 22, there were over 7,750 demonstrations centered on police brutality against Black people and systemic racism in the U.S. across more than 2,440 locations in all 50 states and Washington, D.C., according to a September 2020 report by the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED).

The summer’s protests spilled across borders: Millions of protesters flooded streets in Brussels, London, Seoul, Sydney, and Rio de Janeiro, among many other places, in solidarity with Black folks in the U.S., as well as with marginalized communities in their own countries.

5 things travelers can do now to combat racism→

The social uprisings of 2020, spurred on by the global COVID-19 pandemic, which further shone a light on social inequities, feel unprecedented. Yet for centuries, people have protested publicly to voice their concerns about political, social, racial, environmental, and economic happenings of the day. History has proven that occupying public spaces is an efficient and effective way to share a message; personal recollections from activists show that protesting is a means for healing. In a time when many people feel powerless, taking to the streets is a way to reclaim a sense of self and control. It is a straightforward answer to the question: When there’s nowhere to make our voices heard, where do we go?

The Nature of Street Protests

Demonstrations in Minneapolis have continued for months as protesters demand police reform and racial equality. While mainstream media coverage initially focused on property damage and violence, 93% of protests across the country have been peaceful since late May.

Still, destruction lingers. Some roads may never look the same, just as few protesters and bystanders may never feel the same.

But of course, that’s the point.

“You’re unlikely to completely change someone’s mind by taking over public space, but if you get a double take or get someone to reconsider for a second… that’s part of the power of taking over the streets,” says Celina Su, the Gittell Chair in Urban Studies at the City University of New York.

Over the summer, Sarah Brown, an Amnesty International area coordinator and Black Lives Matter member in Seattle, protested a juvenile detention center on a main street. “If people weren’t aware of the protest, they stopped by for a minute or two and talked to us. They’d say, ‘Is there anything I can do?’ So they’ll sign a petition or sit for a minute,” she says.

Though a lot of effort goes into organizing a street protest, with organizers disseminating information across social media channels and rallying different organizations to support a single moment, they can also be more fluid and unpredictable—especially compared to those held indoors. “In an administrative building, you’re making people question how the key administrator, college president, or the CEO usually runs things. It’s a very focused audience and [there are] probably specific policy demands,” says Su. “Outside, it’s harder to make specific policy demands and you probably don’t have as much power over who joins you and who doesn’t.”

But the organic nature of street protests can have its benefits. In the fall of 2014, tens of thousands of people gathered for sit-in street protests demanding more transparent elections in Hong Kong. At one point during the 79-day uprising, there was rain in the forecast, so protesters brought umbrellas. “Even though it was totally peaceful at the time, the police started teargassing and pepper-spraying everyone, and everyone used their umbrellas for protection,” says Su. The unplanned and very public occurrence “became such a powerful visual on the news that night that it became known as the Umbrella Movement.”

When Place Becomes Synonymous with Protest

A powerful protest can alter the very nature of a public space, creating a symbol of the protest sentiment for years afterward. Sites like Tahrir Square in Cairo, a large traffic circle that served as the home base of the 2011 Egyptian Revolution, and Place de la Bastille in Paris, formerly the site of a fortress that was seized during the French Revolution, are just two examples of places that will never be extracted from their protest history.

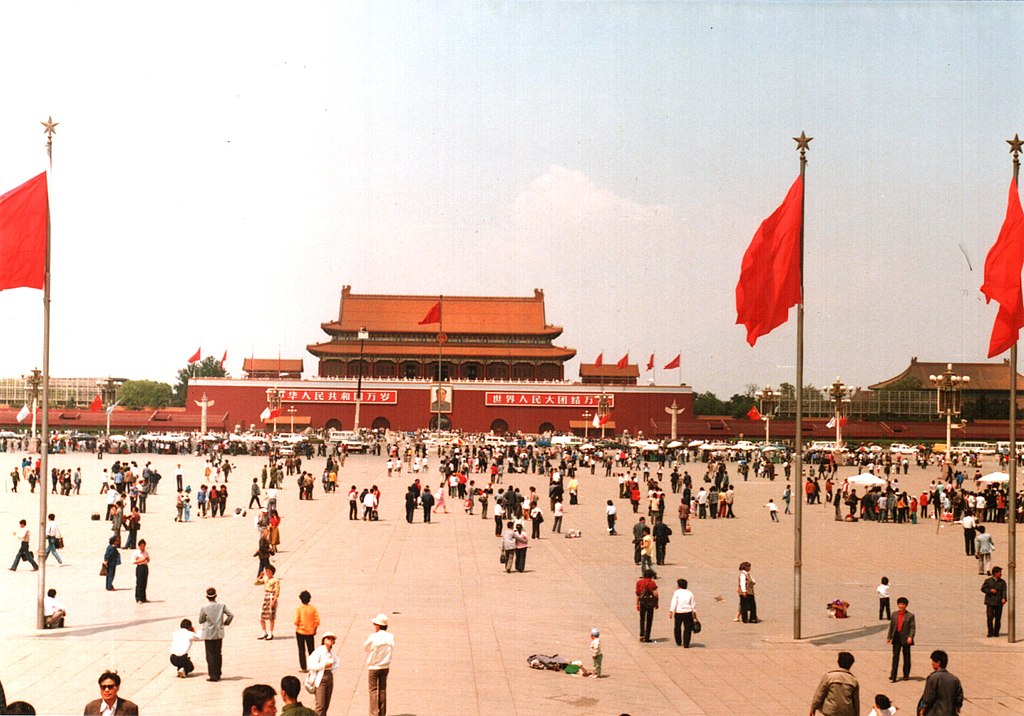

Dr. David Meyer, a professor of sociology at UC Irvine, also points to the incident at Beijing’s Tiananmen Square in 1989. The student-led, pro-democracy, pro–free speech protests, which lasted about three months, ended when armed troops and tanks fired at the demonstrators. As many as 10,000 people were killed. “Now, the square is covered with police all the time to make sure something like that doesn’t happen,” he says. Police presence, however, serves as a constant reminder of the site’s violent past.

Then there’s the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama. In 1965, state troopers stopped and brutally attacked nonviolent protesters who were marching for African Americans’ right to vote. Later known as Bloody Sunday, the televised incident was a major turning point for the civil rights movement.

The bridge was declared a National Historic Landmark in 2013. And with the death this year of Representative John Lewis—who sustained a cracked skull from a state trooper’s nightstick while helping to lead the march—there has been renewed interest in a campaign to rename the bridge in his honor. Though the bridge is still named after a former Confederate general and Klu Klux Klan leader, it’s certainly not his actions that have made the Alabama bridge memorable.

No More Business as Usual

In 1964, antiwar and civil rights activists attempted to shut down the World’s Fair in New York. “They said ‘in a world that’s not fair, we shouldn’t be making it so easy to go to a world fair,’” says Meyer. “So the Brooklyn chapter of the Congress of Racial Equality [CORE] planned a stall-in to shut down the highways.”

CORE announced that over 1,800 activists would use their cars to stall out on the roads for an event that was projected to have 250,000 visitors from all over the world on opening day, causing a media maelstrom. Government officials went into a frenzy, exponentially increasing police presence across the city and threatening legal action against any protesters. President Johnson, who at the time still hadn’t been able to get the Senate to pass the Civil Rights Act, was scheduled to speak that day.

The scheduled protest caught the eye of Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. “Which is worse, a ‘Stall-In’ at the World’s Fair or a ‘Stall-In’ in the United States Senate?” the civil rights leader asked. “The former merely ties up the traffic of a single city. But the latter seeks to tie up the traffic of history, and endanger the psychological lives of twenty million people.”

Ultimately, only a few dozen activists stalled out their cars on the highway and protested at Johnson’s speech the day of the fair. “They didn’t cause too much disruption, but the threat of setting it up got national attention,” Meyer explains.

Less than half of the projected visitors wound up trekking to the World’s Fair on opening day. It was “a day in which the President came to the world of fantasy and encountered the world of fact, a day millions will never forget,” said Michael J. Murphy, who served as the New York City police commissioner at the time.

“The greatest power [protesters] have is the threat of disruption,” says Su. “There’s something about taking over the streets that says, ‘This is what we could do. We could interrupt traffic for a very long period of time. We are putting ourselves on the line. This is how much this means to us.’ That’s probably one of the most powerful ‘weapons’ or strategies that activists can have.”

“Whose streets? Our streets!”

Governments understand the power of streets. In August, the government of Belarus employed the police and army to block all roads in and out of the capital city, Minsk, early in the morning on election day, anticipating that the opposition party would make a powerful showing.

When the incumbent leader Alexander Lukashenko won in a seemingly dubious landslide, thousands of people took to the streets to protest his re-election. According to AP News, nearly 7,000 people were detained and hundreds were brutally beaten by police during the first several days of post-election protests, and in late September, Lukashenko closed the borders to the country—but this hasn’t stopped the protesters.

When citizens don’t feel that their voices can be heard through proper democratic channels, they are left with few choices but to take to the streets. While U.S. citizens have the right to assemble—even if many locations require permits—many countries, including Belarus, maintain tight restrictions on protests, which is exactly why people feel compelled to protest “even when they’re not permitted,” says Su. “The point of protest is to question power.”

Though the situation in Belarus is still evolving, there’s no doubt the thousands of protesters demonstrating over the last several months have made a powerful statement by risking their lives and livelihoods to affect the country’s relationship to democracy for years to come.

Protest as Catharsis

Street protests can be as much about healing as they are about contesting power or making a statement.

Nhawndie Smith was one of several activists who joined a block party during the weekend of Juneteenth in Durham, North Carolina, this summer. “Folks were eating food, people were doing different coordinated line dances—it was really beautiful,” they recall. “Then a few folks spoke to what our communities have been consistently demanding: less money for funding of police and more funding to help folks get what they need.” The block party was held near a new multimillion-dollar police headquarters where activists painted the word “defund” and an arrow toward the building. On the same block, activists wrote “fund” in front of a social services building.

After the block party, activists led a march as protesters sang and chanted in chorus. The marchers stopped at the Durham County Jail. “Folks were lining up, making a circle around the jail, and chanting ‘we love you, we see you, and we support you’ to folks inside—knowing that inside prisons and jails across North Carolina and beyond that there are cases of COVID,” says Smith. (According to the Equal Justice Initiative, Incarcerated people are five times more likely to contract coronavirus compared to the nation’s overall rate, and there have been many calls to release people who are not a threat to public safety or who are eldery.)

The demonstrators then wrapped the jail in hazard tape “to symbolize the hazard of this violent monument. We know that being incarcerated traumatizes and leads to the death of many Black and brown people,” says Smith. “In that moment, we were holding them in our hearts, singing songs, and saying prayers for the folks who are inside, who have been experiencing the isolation that people who are not in cages or incarcerated in some form have been feeling since COVID.”

For them, this was more than a protest—and there was no better location to unload the community’s grief. It felt “very spiritual and ancestral,” says Smith.

The Slow Road to Progress

Participating in public demonstrations can feel exhilarating and empowering, but Su also notes the frustration that comes with protesting—and the need to be in it for the long haul, “especially if it’s something you believe in.” Thinking back to the beginning of America’s war against Iraq and Afghanistan, Su says, “There were hundreds of thousands of people in the streets. That was so many years ago, and the war has not ended, really, with Afghanistan. Sometimes, you feel frustrated that you’re all in this together and policymakers are still not listening.”

Three first steps toward an anti-racist travel industry→

She also points out that while the racial justice moment of this summer seems momentous, it succeeds years of organizing. The call to defund the police, for instance, was not conceptualized in 2020. “The Movement for Black Lives articulated that as a key demand in their platform years ago—and that platform was formed by over 50 organizations associated with Black Lives Matter.

“There’s been a huge amount of work over the past few years so that this summer it was clear across the whole country that the demands at these uprisings were about systemic racism and not a few bad apples,” she says. “It’s so impressive.” While each protest may not lead to an immediate policy change, it’s “still a step towards different policy framing… and it also does something for the soul of the participants,” says Su. “The struggle itself is important.”

There may be a long road ahead, but the streets are open to all.