A look inside the hip hop scene in Tokyo, Japan, from its rise in the 80s and 90s to now—plus, the best places to listen to hip hop while you’re in town.

Like most great music scenes, hip hop in Tokyo emerged from the underground. Fans credit DJ and streetwear idol Hiroshi Fujiwara for introducing the music to Japan in the 1980s after he fell in love with it during a trip to New York City. Bringing American records home, Fujiwara began spinning tracks in clubs throughout Tokyo. It was a style of music the country hadn’t yet been exposed to—and at first, it was scarcely recognized.

In the early days, hip hop was largely ignored by major Japanese record labels and listeners; the community remained intimate, confined to discreet venues and covert gatherings. But eventually, the music gained visibility through media, making itself known through cult-classic documentaries and television shows.

“I would watch the Thumpin’ Camp DVD and it featured NIPPS, a Japanese rapper, who would ‘spray poison’—Japanese slang for how rappers flow or spit their rhymes,” says Chigasaki-born artist Ill Effects. The film adaptation of the 1996 Japanese rap festival inspired him to dive headfirst into the art. “It was my first time seeing it done live. I was shocked.”

“Hip hop–based television shows made a big impact and made the rap community bigger,” agrees Tokyo-based rapper Leon Fanourakis. “There was a freestyle rap battle show I watched when I was still in high school—that’s when hip hop became more noticeable.”

The creative’s local guide to Tokyo →

As the genre gained traction, more artists began to try their hand at the craft. They drew influence from the American scene, admiring its fashion and culture from the other side of the world.

“People guessed things about American rap culture from the media, similar to people in America and their ideas about Japan now,” says radio host Jayda B., founder of feminist music collective Bae Tokyo. After attending college in Japan, she established her career on air in Atlanta—a capital of modern American rap—but soon returned to Tokyo, working with local artists and getting a firsthand look at the globalization of hip hop.

“It’s interesting to see just how moving [rap] is for people of all different backgrounds and who speak different languages, and how immersed people want to be in the culture because they think it sounds good, it feels good, it looks good,” she says.

The packing essentials music lovers need →

Tokyo’s earliest rappers followed their American counterparts in language as well. Initially, Japanese acts tended to translate their lyrics to English; Japanese, they feared, might not flow as easily.

“I used to only listen to American rap,” says Fanourakis, whose original inspirations were American rappers like Busta Rhymes, A$AP Ferg, and ScHoolBoy Q. “I had this idea that Japanese rap songs were harder to dance to. I also have many friends from different countries, and they would ask me why I would [bother to] rap if I couldn’t even speak English.”

Fanourakis continues: “That’s when I decided I wanted to make Japanese rap that would make those who don’t understand [the language] like it too. I wanted to develop a style that made Japanese rap sound as cool as American rap.”

Eventually, many artists felt the same, creating tracks using exclusively Japanese lyrics that distinguished them from their international peers.

Views from quarantine in Tokyo →

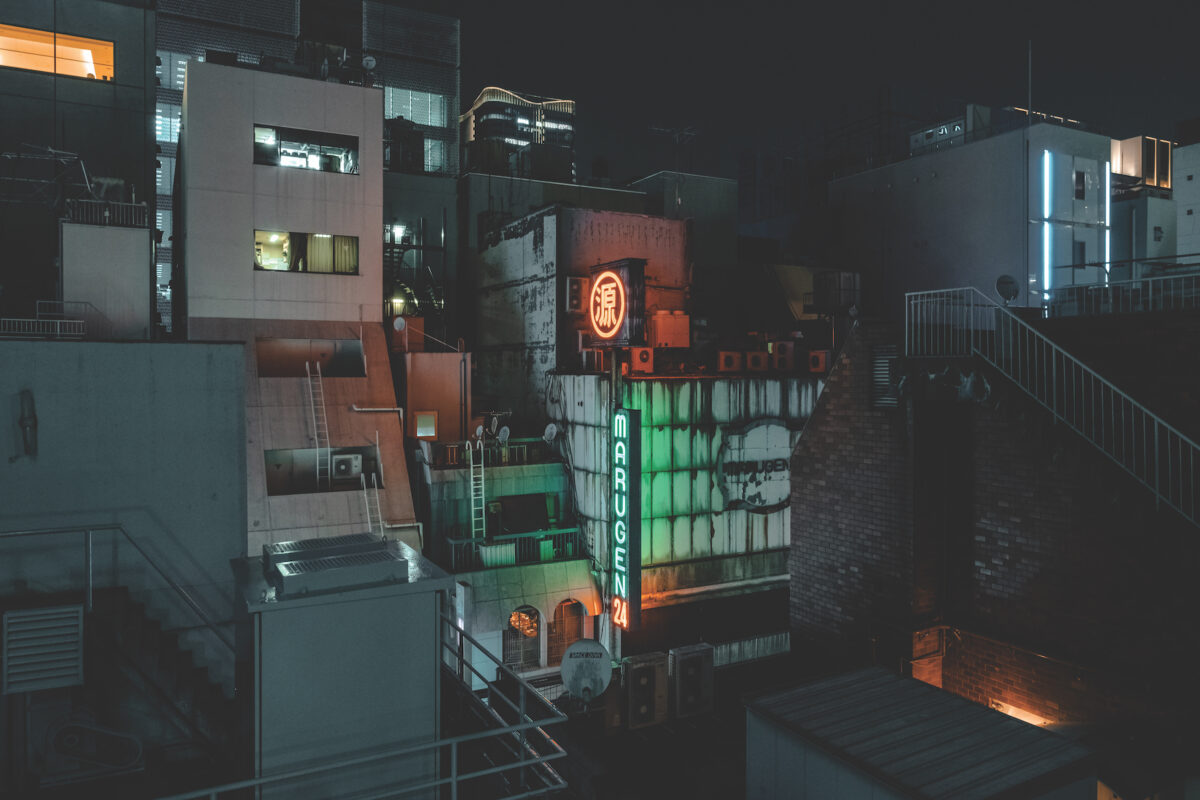

Finally, in the ’90s, hip hop in Tokyo boomed; acts like King Giddra and Buddha Brand debuted to commercial success, hip hop-centric clubs like Vuenos (now closed) and Harlem opened, and artists began making appearances at packed nightclubs and bars.

Places like Yoyogi Park also became popular for ciphers, where anybody interested in freestyling, rapping, or breakdancing can show off their skills. Ill Effects still lives in Chigasaki, but commutes to Tokyo every weekend to enjoy the rap community. On Saturdays in Yoyogi and Sundays in Shinjuku, he hosts block parties that turn the average city block into a club in its own right. Performing his own tracks live, accompanied by local DJ Vulgar, the series invites locals to come together and celebrate the music they love.

“From spring to fall in Yoyogi, the parties get pretty crowded,” says Ill Effects. “But we’re doing something nobody else is doing, so that’s why the people who come are so supportive.”

Perhaps most famously, the 2000s saw the rise of the late Jun Seba. More commonly known as Nujabes, the legendary Tokyo-born producer pioneered the style of Japanese hip hop best known across the world today: lo-fi hip hop. Known for its steady beats, atmospheric instrumentals, and samples of ’90s anime dialogue, online beat-makers and radio stations like ChilledCow took after Nujabes to establish a style of Japanese hip hop with a sound all its own: dreamy and slow, the kind of easy listening that induces unconscious head-bobbing and instant relaxation.

Ultimately, Tokyo’s hip hop scene speaks to the beauty of globalization—what began as an imported trend is now not only a staple of the city, but an ebb-and-flow between an international community. After initial influence from overseas, Japanese culture has doubled back to influence North American talents: Artist Takashi Murakami famously designed the cover for Kanye West’s Graduation, and hip hop–inspired anime like Afro Samurai and Samurai Champloo became two of the most commonly sampled scripts in the lo-fi tracks so popular with listeners abroad.

“It was part of my goal to be a bridge that could connect people, so that we could build this community and understand one another regardless of language, and make things more about community, creativity, and the music itself,” says Jayda B., who recognized the desire from both sides of the world to draw inspiration from one another’s work. And while artists from rap’s birthplace and its hottest new scene may perform in different dialects, nothing about the genre’s dedicated acts or fans has ever been lost in translation.

Where to Hear Hip Hop in Tokyo

Harlem

Named for the New York neighborhood that gave birth to a legion of world-famous names and a renowned style of rap, this nightclub in Shibuya hopes to follow in the footsteps of its American namesake as a meeting ground for Tokyo’s new and established talent.

Bloody Angle

Located in Shibuya, this record bar draws Tokyo’s fashion and music communities to sit amongst vintage décor, sipping inexpensive drinks while listening to carefully curated old-school tracks.

WREP Bar

Touting itself as Tokyo’s “home of hip hop,” this outpost is the physical manifestation of WREP, a 24-hour, 365-day radio station dedicated to the genre. Founded by Japanese hip hop star Zeebra, this intimate space for live DJ sets keeps the party going until five in the morning.

Sound Museum Vision

Often shortened simply to “Vision,” this megaclub in Shibuya hosts both domestic and international acts, packing partygoers into three floors of electronic, rap, and house music.

Yoyogi Park

This famously serene park has a duality to it. Every Saturday, rappers and hip hop fans from across the city and beyond gather for a freestyle-rap block party. Established by artist Ill Effects, the series provides a fun musical interlude for visitors wandering between peaceful Meiji Shrine and their next destination.

Or check out…

ChilledCow Radio

A pioneer of the 24-hour internet radio stations for Japanese-inspired lo-fi hip hop, ChilledCow features soothing tunes that will ease you into a tranquil state with smooth beats and an anime-style backdrop that changes every 12 hours.

Leon Fanourakis

Born in Yokohama to musically inclined parents, Tokyo-based rapper Leon Fanourakis achieved national fame at just 17. Now signed to Tokyo hip hop label 1% (ONE PERCENT), he released his latest album, CHIMAIRA, in early 2019 to industry-wide acclaim.

Bae Tokyo

Founded by radio host Jayda B., this feminist collective focuses on promoting women DJs, rappers, and hip hop artists in Japan and throughout Asia, as well as throwing parties and events for female creatives in Tokyo.